This material belongs to: WSJ.

As offshoots of Car Wash probe fall to other courts, country’s most famous judge says ending graft ultimately depends on politicians changing laws.

CURITIBA, Brazil—Brazil’s Car Wash corruption investigation has in the last three years led to over 160 convictions, inspired a blockbuster movie and implicated hundreds of politicians, including the current president and four of his predecessors.

But as Judge Sergio Moro, who has headed the epic probe, prepares to finish the core investigation under his jurisdiction, he stressed that Brazil’s fight against corruption ultimately depends on the will of the very politicians who perverted the country’s political mores to change the laws and prevent their successors from doing the same thing.

“We shouldn’t be under the illusion that the problem of corruption can be solved merely by the criminal justice system. It just treats its most evident symptoms,” said Mr. Moro, 45, in a rare interview in this southern city.

Without new legislation that dramatically alters how money is spent in politics, he said, Brazil is in danger of following the same path as Italy. There, the Clean Hands investigation in the 1990s, which he used as a model for Car Wash, led to a power vacuum, fueled a degree of cynicism about judicial power and ultimately did little to reduce graft in the long term.

Super-Moro, as the judge is known by his followers, has made many enemies in Congress, where targeted politicians have called him a wannabe celebrity and an autocrat. Large-scale public protests over corruption have faded in Brazil, though analysts differ on whether that is because of apathy, preoccupation about the country’s economy or confidence that the judiciary can do its job without support on the streets.

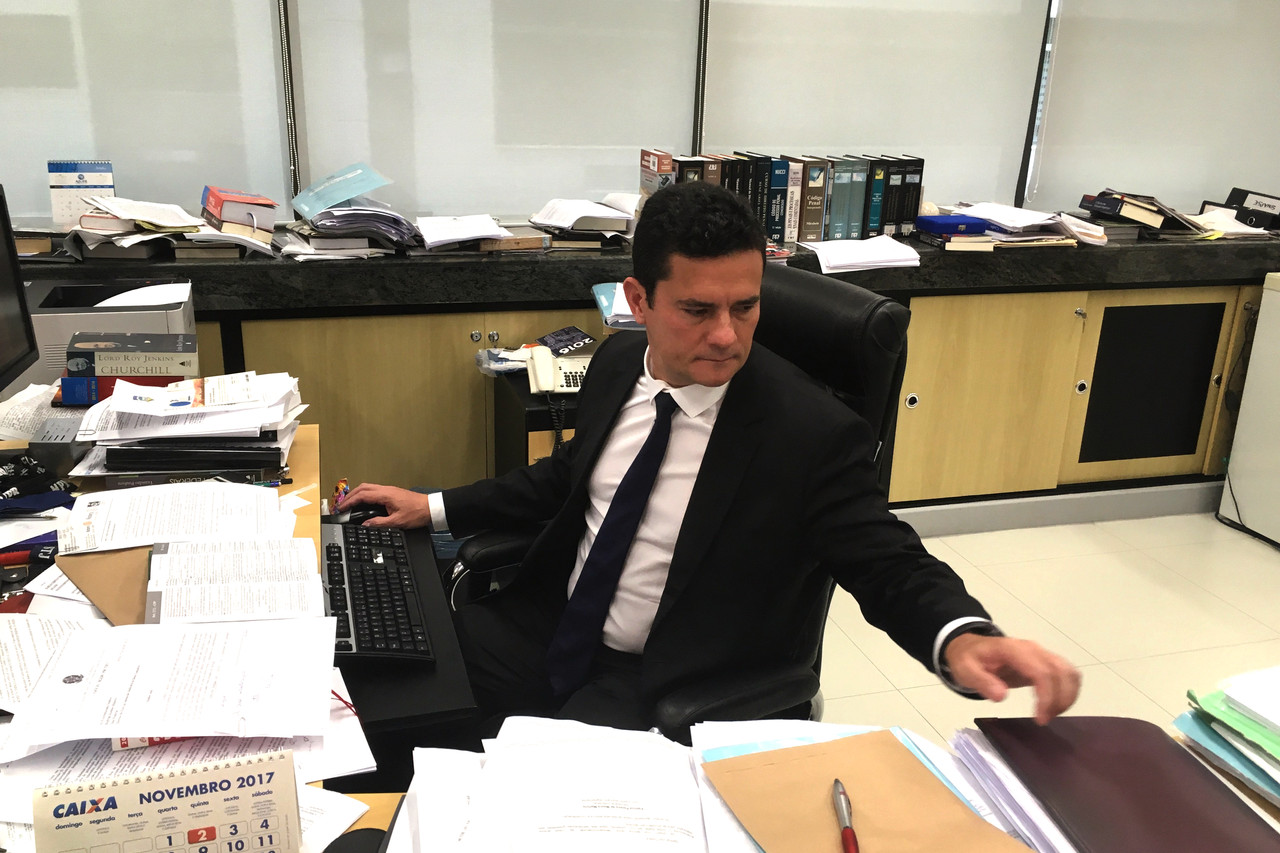

Strewn with documents and books on everything from Winston Churchill to constitutional law, Mr. Moro’s office in this otherwise humdrum provincial city has been the hub of an investigation that has rocked Latin America and turned the shy lower-court judge into an internationally recognized figure.

Mr. Moro, a part-time law professor who briefly studied at Harvard, landed the case of his lifetime in 2014 when a local money launderer led him to uncover Brazil’s largest-ever corruption scheme at state-controlled oil company Petróleo Brasileiro SA or Petrobras.

As most of Mr. Moro’s trials in this case near completion, the investigation will now center on courts in other jurisdictions investigating offshoots of the original corruption network. Also continuing the work will be regional judges hearing appeals and the Supreme Court, which is the only body in Brazil allowed to sentence sitting politicians.

Mr. Moro urged lawmakers to consider changes to protections offered to politicians in office, and said Brazil must cut the cost of its expensive election campaigns and end political appointments at state companies.

“It’s necessary for other institutions to also do their part with reforms that reduce the opportunities and incentives for corruption,” Mr. Moro said.

The judge’s comments come as Brazil’s Congress has done little to cut campaign costs, instead approving this month a controversial new bill to increase public funding for politicians after attempts at wider political reforms failed.

Operation Car Wash, named after a gas station used to launder cash, has now extended well beyond Petrobras, implicating scores of multinationals such as construction group Odebrecht and meatpacker JBS, as well as the nation’s top political parties. Companies paid multimillion-dollar bribes in exchange for contracts, cheap state loans and other favors. Politicians used the cash to fund lavish lifestyles and their election campaigns.

Mr. Moro’s team in Curitiba has sentenced more than a hundred people for involvement in corruption crimes that amount to about $2 billion. That has won him praise here and beyond Brazil and raised hopes about an end to crony capitalism and impunity.

Mr. Moro owes his success partly to legal changes in 2013 that paved the way for tell-all plea bargains. He also had the advantage of operating out of a city distant from the capital, Brasília, with a well-funded team of prosecutors and police officers.

It hasn’t been just defendants, however, that have criticized Mr. Moro for holding suspects in jail under preventive custody for months at a time. “Car Wash started well,” said Daniel Vargas, a law professor at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation in Rio de Janeiro. “But it got lost along the way, contaminated by applause and by its popularity.”

Criticism is normal in a democracy, Mr. Moro has said, adding he was “infinitely hopeful” about the ability of ordinary Brazilians to hold their politicians to account and vote for a better class of lawmakers.

But he said progress in rooting out corruption would be slow, and his hope is no guarantee of success. In Italy, the Clean Hands graft probe created a power vacuum that primed the rise of Silvio Berlusconi, a media tycoon and four-time prime minister whose terms were marred by corruption allegations and sex scandals and who was convicted of tax fraud.

Some Brazilians say the only way to keep the anticorruption drive moving is for Mr. Moro to become president and lead the upending of the political status quo.

Mr. Moro has repeatedly denied he would run for office, even though recent polls show he would be tied in a runoff vote with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s popular former president. Mr. da Silva is planning a comeback ahead of next year’s October election despite Mr. Moro having sentenced him in July to 9½ years in prison for corruption. Mr. da Silva is appealing the ruling.

“If I entered politics it could create the wrong impression about the motives of my current conduct,” he said. “It’s possible to positively influence society without being president of the republic.”

The once unknown Mr. Moro is now applauded by fellow diners in restaurants and sometimes mobbed by well-wishers in supermarkets. There are carnival masks in his likeness, bumper stickers bearing his name and, in his inbox, a deluge of desperate requests from across Brazil to help solve even the most obscure cases.

“In Brazil we have a way of believing in miraculous solutions, that ‘X’ will happen and this will forever change the history of the country,” Mr. Moro said.

He predicted that other important investigations could come his way. “Who knows,” he said, “maybe in a few years I will have other cases in my hands that are just as big.”