This material belongs to: The Telegraph.

Anyone who thinks the pen is mightier than the sword may have their faith shaken by visiting the spot where Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered. Malta’s most influential journalist was driving from her home in the village of Bidnija one afternoon last October when a remote-controlled bomb detonated inside her car.

The blast was so powerful that it tossed her vehicle far into a nearby field, where her son Matthew found his mother’s body amid the blazing wreckage. Three months on, a banner demanding ‘justice’ still flutters over piles of withered bouquets left by mourners. ‘Daphne, your pen is mightier than Semtex,’ one tribute says. ‘What you wrote and what you uncovered cannot be blown to bits.’

Galizia’s rented Peugeot hatchback wasn’t the only thing destroyed that day. Also shattered was Malta’s international reputation as a safe, stable outpost of southern Europe, where journalists could operate without fear of intimidation or assassination. It is fair to say that Galizia, 53, had already done much to undermine that reputation through her blog, ‘Running Commentary’.

Likened to a one-woman WikiLeaks, it shone a harsh light into Malta’s shadier corners, painting a very different picture of the country most Britons think of as a picturesque holiday destination. Britain has strong links to Malta – it was a British colony for 150 years – and the island still boasts red pillar boxes. In its capital, Valletta, a museum displays the George Cross the island won for holding off the Nazis in the Second World War. But the Malta that Galizia wrote about had rather less to celebrate.

Over the years, she chronicled what she saw as its alarming moral decline, detailing everything from corruption among Malta’s small, incestuous political elite through to concerns that the tiny island had become one of the world’s most popular havens for dodgy money.

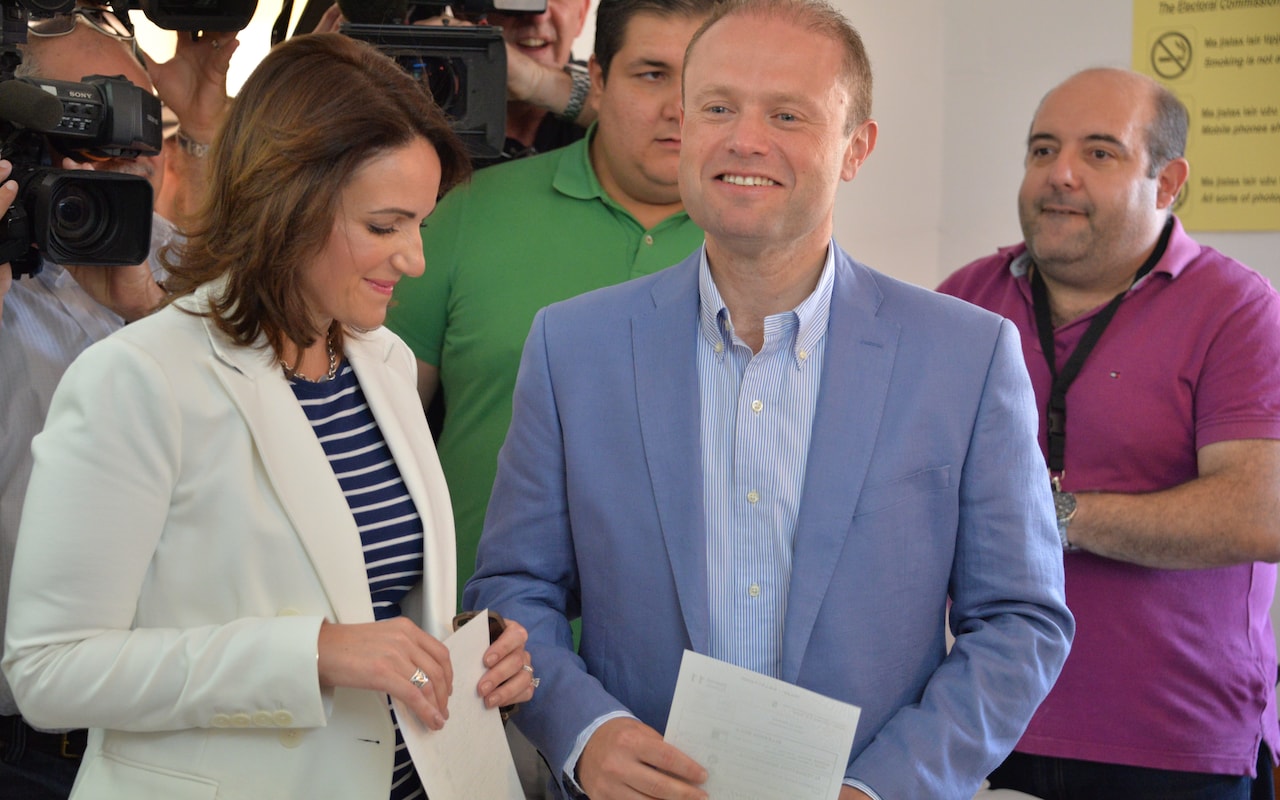

‘People marvel at the way the Maltese economy always seems to be thriving,’ she wrote. ‘Only a fool would think it is all legitimate.’ Last summer, her pen even triggered a snap general election, when she alleged that the wife of Joseph Muscat, Malta’s centre-left Prime Minister, had an off-shore bank account to launder money for the family of Ilham Aliyev, the authoritarian President of Azerbaijan.

‘Whether it was fuel smuggling, drug barons or our shady government, the list of suspects in her murder is endless,’ says fellow Maltese investigative journalist Caroline Muscat (no relation to the Prime Minister). ‘Daphne’s voice was unique, speaking out in a climate where we are facing the collapse of the rule of law.’

At the end of last year, just as fears were growing that Galizia’s killers had disappeared without trace, three men were charged with her murder – brothers Alfred and George Degiorgio, and Vince Muscat (also no relation). But while all three are reported to be members of the local criminal underworld, none had ever appeared in Galizia’s blog, or had obvious cause to bear grudges against her. Police now suspect that if they did carry out the killing – which they deny –they did so for someone else. Who though?

For the island’s 430,000 people – crammed into a space the size of the Isle of Wight – the case has become a compelling, claustrophobic whodunnit, a Scandi-noir political thriller with better weather. Was it the secret arm of the state, keen to silence a critic? A local Mafioso, angry at having his political connections exposed? A hit squad from Azerbaijan, a country notorious for taking revenge on unfriendly journalists? Or a player in a scandal that Galizia hadn’t even published yet, and which now may never be revealed? Prime Minister Muscat enlisted the FBI amid claims that Malta’s small police force was neither experienced nor competent enough to get to the bottom of what happened. But, even after the arrests at the end of last year, Galizia’s family believes the government is not interested in discovering who employed the ‘trigger men’.

They suspect that whoever ultimately ordered the killing was connected to Malta’s ruling class, and that suspects ‘in or close to government’ may be being protected.

‘A culture of impunity has been allowed to flourish by the government in Malta,’ says Galizia’s son Matthew, himself an investigative journalist. ‘If the institutions were already working, there would be no assassination to investigate – and my brothers and I would still have a mother.’

At the time of her death, Galizia’s family point out, she had 42 outstanding writs piled up against her in the local law courts, including one from the Prime Minister himself. Nor was their confidence in the inquiry boosted by comments from a Maltese policeman who wrote, ‘Everyone gets what they deserve’ on Facebook within hours of her death.

Indeed, for the thousands who demonstrated after her death, Galizia is already a martyr to the truth. In the words of the makeshift memorial to her in Valletta – set up opposite the law courts’ neoclassical façade – ‘she was killed because she mattered’.

The case has also caused alarm in the upper echelons of the European Union, which is due to celebrate Valletta this year as European City of Culture.

After her death, the European Parliament passed a motion on ‘serious concerns’ about democracy and the rule of law in Malta. Yet to complicate matters further, not every Maltese citizen subscribes to the narrative of Galizia as a slain journalistic icon. The President of the European Parliament, Antonio Tajani, who attended her funeral in November, said she ‘epitomised everything that is good about that profession’. But critics say she represented much that was bad about it too.

While her blog was witty and perceptive, much was based on hearsay, not facts, her detractors say. She was partisan, disparaging Muscat’s ruling Labour party, but less so the rival centre-right Nationalist Party representing Malta’s ‘old money’ Anglophile elite. She was also prone to delivering vicious personal attacks, not just on the great and not-so-good but on the rank and file, whom she often dismissed as hamalli (Maltese for ‘chav’).

According to Saviour Balzan, editor of Malta Today, if police wanted to question everyone who bore a grudge against Galizia, ‘they would have to arrest thousands of people. Everyone describes her as a journalist, but I wouldn’t even count her as that. She copied and pasted, and was a magnet for gossip, who would publish anything people told her.’

Yet Galizia’s blog did reflect a wider unease that Malta, 60 miles south of Sicily and 200 miles north of Libya, has attracted unsavory players in recent years. Since 2015 there have been six other car bombings, all unsolved but mostly linked to fuel- smuggling rackets from Libya. Malta has always been a place where Libyans have done a certain amount of dirty work – in 1988, it was where the suitcase that carried the Lockerbie bomb was first introduced into the airline system.