This material belongs to: Der Spiegel.

A potentially vast corruption scandal threatens to overrun Airbus, with a Paris-based sales group suspected of having paid bribes around the world. German CEO Tom Enders is leading the clean-up effort, but documents reveal that he might not be as spotless as he claims.

This is a story of a global company. About its secrets. It is the story of a corrupt corporation.

The company is called Airbus.

It is a story that begins with the word “shit,” with a Dacia Duster and with a tiny company that could cost the CEO of Airbus his job. Because he, too, apparently has a bit of a skeleton in his closet.

But first things first.

First, the word “shit”: It is June and top company managers have gathered for a meeting in Toulouse, France. CEO Tom Enders is standing on the stage. He has been with the company for 17 years, but his English is still less than fluent and he speaks with a heavy accent. But the message to his top managers is nevertheless crystal clear. “If there are still people in this room, that believe we should put the shit under the rug — then I would have to say, I give up on these people.”

Enders, 58, speaks of a past that Airbus has long sought to deny, years in which the company partly relied on bribes as it rose to become the world’s second-largest airplane manufacturer, after Boeing. And Enders speaks of a present in which all of that is beginning to come out — a situation that poses grave dangers to the company he runs.

At issue are potential multibillion-euro fines and multibillion-euro losses. Indeed, the very survival of Airbus, with its 134,000 employees and its annual turnover of 67 billion euros ($78.6 billion), could be at stake. Hence, the message from Enders to all those who haven’t yet got the message, to those who think they can just carry on as before, including the bribery: “Leave this company rather than make us take you out of the company. Because we’re in a dead serious situation, dear colleagues.”

Which brings us to the Dacia Duster. At the end of May 2017, in the Romanian city of Bacau, a man was finally able to fulfill his dream of buying a new car, having managed to save up enough money for a diesel vehicle from the affordable Dacia brand: a special edition Black Shadow Duster. To make the purchase, though, Constantin Ster had to take out a loan – and a quick glance in the commercial registry provides a clue as to why: Last year, his company only had 1,300 euros in turnover, and the company before that went belly up.

Straw Man

Ster is bankrupt and not exactly a big fish. Yet he is thought to have pocketed more than 5 million euros from the airplane manufacturer, which was still called EADS at the time. The money was allegedly in exchange for the procurement of orders. But Ster seemed bewildered when he was faced with such accusations from investigators. If he hadn’t received the money, then where did it end up, they asked? What role was played by Ster, owner of a 15,000-euro car bought on credit, the straw man of the corporation?

And now, to the small company: State prosecutors from Munich interrogated the Romanian man all the way back at the end of 2015 and they have interviewed many other witnesses since. The Bavarian investigators have been on the case for five years and are likely to hand down indictments in the coming months — against a whole list of former EADS executives and their henchmen.

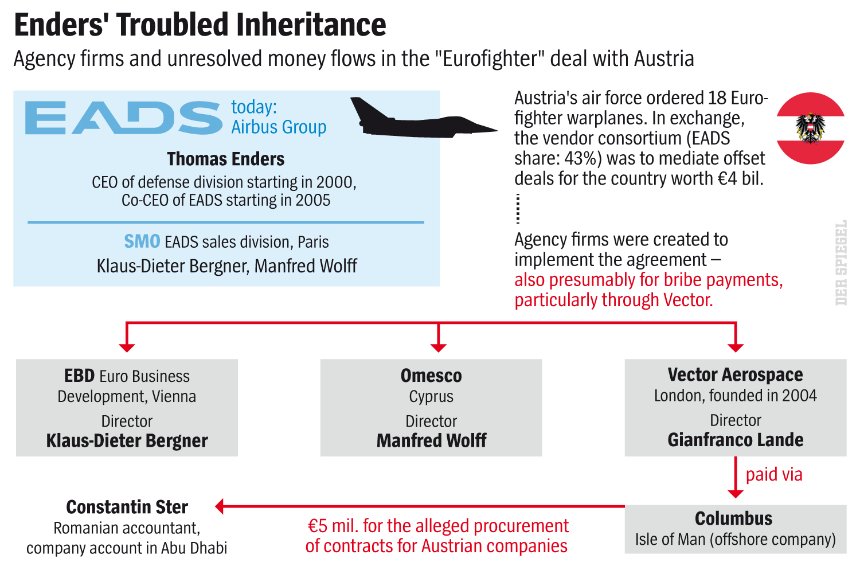

They are suspected of having constructed a vast empire of corruption for the company — and in the center of it all stands Vector Aerospace in London, a two-person company that received 114 million euros from EADS. What did Vector do for all that money? Investigators have only been able to find records pertaining to 9 million euros. The rest was distributed to shell companies in places like Hong Kong, Singapore and the British Virgin Islands. It would seem to have disappeared.

Until recently, it had looked as though that network of shell companies only pertained to the sale of 18 Eurofighters to Austria, built by a consortium led by EADS. State prosecutors based in Munich wrote in a supporting document from December 2016 that “significant sums of money” from the Vector kitty were “to be used for bribery payments to decision-makers … in Austria.” The bribes were to ensure that Vienna placed its warplane order with the Eurofighter consortium.

But apparently, that wasn’t all. Now, there are indications that the millions of euros that came from Vector and flowed via the Romanian man actually ended up in the passenger jet business. And that has led to suspicions that Vector actually served the entire company as a source of bribes. Vector, the Munich prosecutors wrote, was also responsible for “keeping concealed money available for future corruption needs” and to keep those funds “separate from EADS assets.” In other words, a slush fund “created intentionally by those involved,” and not just for the fighter plane order from Austria. It seems likely that the suspicions will end up in the formal indictment before long.

If all of the above is confirmed — and Airbus denies the accusations in this case — that would be bad enough for Tom Enders. It would, in fact, be “shit.” But even before the dubious company Vector was founded in London in 2004, there had been another company in Cyprus. It, too, is thought to have received a significant amount of money from EADS, apparently also to drum up business to boost the Austrian economy. That was the promise EADS made to Vienna in exchange for the Eurofighter order. And the predecessor company in Cyprus was also dubious. And who approved its founding according to the minutes of the relevant meeting? Tom Enders. And who received a long memo when Vector took over? Enders again. The same man who is currently posing as the anti-corruption superhero.

Parallels with Siemens

All of this adds up to a potential Siemens sequel for the German economy, one which has gone virtually unnoticed by the public at large. A new global bribery scandal, similar to the earthquake of corruption that rocked the Munich-based industrial giant in 2006, and continued for years afterward. In Britain and France, anti-corruption agencies are currently investigating Airbus, while Munich-based public prosecutors are doing the same in Germany together with their counterparts in Vienna. Airbus has submitted a voluntary disclosure in the UK. And suspicious cases have begun popping up around the world, including in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, China, Tunisia, Kazakhstan and Mali.

The parallels to the Siemens scandal are difficult to ignore. Both companies do business around the world, including in countries thought to be particularly corrupt, and both did business with fly-by-night companies and employed slippery consultants who received millions of dollars to set up business deals, likely by way of bribing politicians and officials. Both corporations likewise developed a company culture of acceptance for the practice, an understanding that things had always been done that way, that everyone else does it too, and that it is, in fact, the only way such a business can be run.

In one respect, though, the case of Airbus is even more explosive. After all, much of the company remains state-owned, with Germany and France together owning a 22 percent stake. That makes the case a political one — and one that could affect the relationship between the two countries. The government in Berlin is eyeing Airbus nervously as the German and French executives in the company attack one another and hate, anger and distrust run rampant. Who knew what, when? Who cast blame at who? Who must now pay? Who will have power in the company when it’s all over? The Germans? The French? The battle for truth has become a battle between two countries.

Internal investigators have discovered the possible payment of well over 100 bribes. And that is just the beginning. “The dimensions of the affair aren’t yet clear, but it is certainly vast,” says one insider. The “cancerous tumor” of which he speaks appears to have infected all of the company’s divisions. It’s not just about warplanes and passenger jets. “Unfortunately, we have found similar problems in the other divisions,” said John Harrison, the company’s group general counsel, at the meeting of top executives in Toulouse. There are good reasons to believe, he went on, “that the investigation goes wider to the other divisions, because we have business partners who worked for all the divisions.”

Enders has been left with little choice other than to make a clean break: He has frozen all suspicious contracts with external consultants who helped fill the order books for Airbus. He has sought the dissolution of a Paris-based sales division — which he refers to as a “Bullshit Castle” due to his belief that it is responsible for many of the dirty deals made with the help of such consultants. And he has fired people and brought in a law firm to look through files and hard drives. He even gave the lawyers his own laptop.

Recently, he also brought in Theo Waigel, the former German finance minister, as a consultant, a move to indicate how serious he is about getting to the bottom of the situation. Most of all, though, it was Enders’ voluntary disclosure in Britain that served as an invitation to state investigators. He is now posing as the kind of radical house cleaner that investigators like to see — as the one that has to remain standing even as others must be sacrificed to show the company’s determination.

The Ire of the French

Enders is playing the role of the disconcerted senior executive and claims he only realized what was going on in 2014 — and that he has been ruthlessly seeking to clean things up ever since. Doing so, however, doesn’t just risk the ire of the French, who view the step to strip power from the Paris sales division as a German attack on French interests.

More than anything, Enders is risking his job. Indeed, it is now coming out that the executive, known for his toughness (his nickname is “Major Tom“), apparently wasn’t interested in uncovering corruption at all for many years. Rather, he played down the problem. And he may even have been an accessory. That, at least, is one reading of the Munich investigation files that DER SPIEGEL and its French partner, the online magazine Mediapart, have obtained.

Back to the year 2000: When Germany, France and Spain created the EADS corporation to break the Americans’ air superiority, particularly that of Boeing, the French didn’t just contribute its defense giant Aérospatiale-Matra. A sales team was also part of the deal — a conspiratorial group that had learned a lesson that comes with selling warplanes: It doesn’t necessarily matter who builds the best planes.

The ‘Bullshit Castle’

In places where fighter jets are symbols of power, particularly in tin-pot dictatorships and banana republics, other rules apply. In those types of places, top military officers want their cut, as do the ministers and government officials involved in such purchases — people who feel their honor has been slighted if nobody tries to bribe them, because it means that they weren’t important enough.

EADS International, the sales division in Paris, whose name later changed to SMO, dealt with such customers. It was the “Bullshit Castle” that Enders talks about today. Most of those working there were the product of the French defense company Matra, but two Germans also belonged to the team: Klaus-Dieter Bergner, the former head of the East German airline Interflug, and Manfred Wolff, who worked for AEG in Asia before his division was bought by EADS. In describing what the business climate at EADS International does to newcomers, a person with knowledge of the company says: “If you put Mother Teresa in a neighborhood with rampant drug use, she wouldn’t remain a saint for long, either.”

Investigators in Munich and Vienna have become convinced that temptation and sin were everywhere to be found in EADS. They took a close look at the 2 billion-euro Eurofighter deal in Austria, the 2003 order for 18 fighter jets. For a long time, it looked as though the Eurofighter, built by a consortium led by EADS, didn’t have a chance against the Saab Gripen, a fighter jet built in Sweden. But EADS emerged victorious, nonetheless — against all odds and, as they say in Austria today, against all logic. In February, Austrian Defense Minister Hans Peter Doskozil finally took the step of filing suit against Airbus, accusing the company of willful deception and fraud. It was a suit that infuriated the company.