This material belongs to: Mother Jones.

“Everyone seems to know (or hope) that the present administration is an exception.”

Jessica Tillipman was recently leading an anti-corruption training in Washington, DC, to a roomful of visiting bureaucrats from Latin America when something odd happened. As she described various measures the United States has in place to guard against self-dealing and conflicts of interest by government officials, she heard snickering.

In the past, she recalls, foreign guests “would look on kind of in awe” as she described the federal government’s elaborate system for preventing graft and corruption. That has all changed since the election of Donald Trump. Now, her international colleagues are quick to point out that the United States can’t even get its own president to abide by the nation’s ethical standards. “It was almost a bit of a joke,” Tillipman, an expert on government ethics and an assistant dean at the George Washington University Law School, says of the recent training. “To have countries with their own distinct corruption issues laughing at our current issues—it’s embarrassing.”

For decades, the United States has held itself up as a pillar of open and ethical government. On many fronts, it has led by example, enacting and enforcing some of the world’s toughest anti-corruption and ethics statutes. It has used its reputation and economic clout to prod other countries to clean up their acts, encouraging them to pass anti-bribery and transparency laws and spending millions of dollars training foreign officials in the ways of good governance—efforts that amounted to a type of soft power, smoothing over trade relations and bolstering diplomatic ties. And investors like the predictability of open government and honest business dealings. Yet interviews with more than a dozen experts show that the United States is rapidly tarnishing its squeaky-clean image.

“It’s hard to put lipstick on the pig: There’s a very, very different perceived reputation now than three or four months ago,” says Nathaniel Heller, who helps oversee the Open Government Partnership, an anti-corruption organization founded in 2011 at the Obama administration’s urging. “It’s particularly acute because of the very real conflicts of interest and entanglements that the [Trump] family and administration seem to be deeply uninterested in trying to untangle.”

Even before he fired FBI Director James Comey, Trump had openly broken with the ethical norms and expectations followed by all recent presidents. He refused to divest from his international real estate and licensing company. (In contrast, Barack Obama declined to refinance his home mortgage and Jimmy Carter sold his peanut farm out of concern that they might be accused of having a conflict of interest.) Trump’s daughter Ivanka and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner—who also haven’t fully divested from their real estate and investment holdings—were appointed as top White House aides to the president. The National Security Council (NSC) eliminated its directorate for good-governance issues, senior White House staffers skipped an ethics training course used by the two previous administrations, and multiple appointees who’d worked as lobbyists were granted secret waivers to serve in the agencies they once lobbied. In July, the top federal ethics watchdog resigned. He explained, “There isn’t much more I could accomplish at the Office of Government Ethics, given the current situation.”

Trump’s own actions—and those of his family and close associates—suggest a president seeking to monetize his office. He spends nearly every weekend at a Trump-branded property such as Mar-a-Lago, which briefly had its own promotional page on the State Department website. Diplomats and industry leaders flock to his Washington hotel in hopes of winning his favor. On the day that Ivanka Trump and her father met with the Chinese president, China approved three of her company’s copyright requests. Kushner’s family firm has touted its ability to grab visas for wealthy Chinese investors. “The stars have all aligned,” Eric Trump recently said. “I think our brand is the hottest it has ever been.”

To make matters worse, Trump and the Republican Congress have started rolling back the Obama administration’s efforts to combat corruption. In February, Trump signed the repeal of a key provision in the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform law that had required US oil and gas companies to disclose their payments to foreign governments. This doesn’t look so good when your secretary of state was the CEO of Exxon Mobil. The Department of the Interior has been backing away from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, which also publicizes payments to governments by energy companies. The Trump administration has yet to say whether it will remain in the Open Government Partnership; if it leaves, the United States will join abstainers such as Russia and Angola.

And there are indications that Trump may try to weaken the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the crown jewel of anti-corruption laws. Even before he ran for president, Trump expressed hostility to the FCPA (Foreign Corrupt Practices Act), which prohibits US companies from bribing foreign officials, saying it puts American businesses at a “huge disadvantage” and that it’s a “horrible law and it should be changed.” Part of this animosity may stem from his own experiences trying to take his brand global. A recent New Yorker investigation found that the Trump Organization may have violated the FCPA as part of a failed development deal in Azerbaijan, widely considered one of the world’s most corrupt countries. (A company lawyer dismissed this claim.)

Trump’s picks to run the two agencies that bring FCPA cases don’t inspire confidence. The head of the Securities and Exchange Commission, a corporate lawyer named Jay Clayton, chaired a New York City Bar Association committee that released a 2011 paper that called enforcement of the law “unilateral and zealous” and recommended “the reevaluation of the United States’ strategy in fighting foreign corruption.” During his confirmation hearings, Attorney General Jeff Sessions pledged to uphold the FCPA, but some experts fear that weakened enforcement could come in the guise of funding cuts. “I would never question the integrity of the people who are pursuing these cases, but you can cut a budget,” says Chris Sanders, a spokesman for Transparency International. “You can reduce the number of investigators.”

Convincing officials in corruption-plagued countries to have the courage to combat graft has always been a tough sell, says Shruti Shah, a vice president at the Coalition for Integrity. Having a president who’s blithely unconcerned about real or perceived corruption only makes it harder. “We can’t tell people in Africa or anywhere else in the world to do anything we’re not doing ourselves.” The day Trump fired Comey, US Ambassador to Qatar Dana Shell Smith tweeted, “Increasingly difficult to wake up overseas to news from home, knowing I will spend today explaining our democracy and institutions.” Mary Beth Goodman, an anti-corruption official in Obama’s NSC, says that if the United States all but abandons this fight, it could kick off a race to the bottom around the world. “Very little gets done without US leadership.”

The administration’s actions have sent “a very bad signal” to its international partners, says Jorge Hage, Brazil’s former anti-corruption minister. The silver lining: “Sooner or later, the US will go back to its traditional policy of promoting and emphasizing public integrity and transparency, and fighting corruption,” he writes in an email. “Everyone seems to know (or hope) that the present administration is an exception, kind of an accident.”

The Art of the Steal

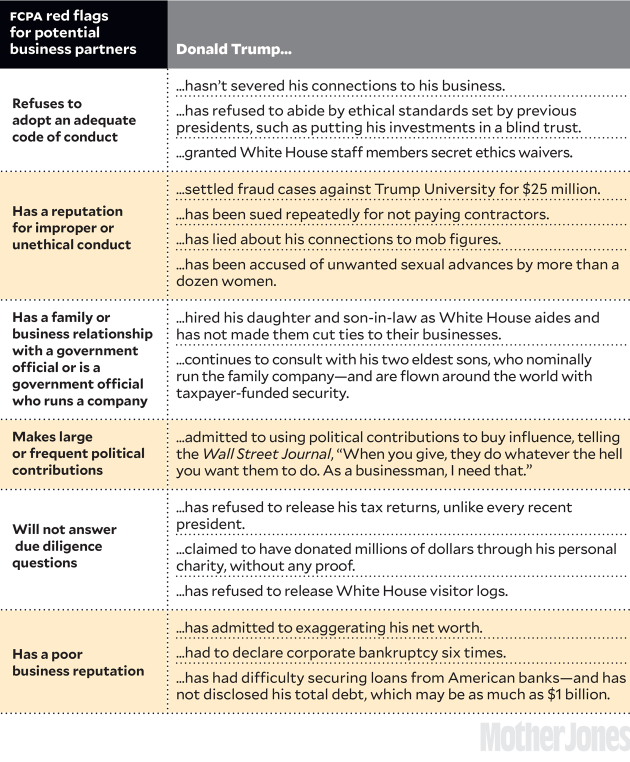

Under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), American companies that operate abroad must screen any potential business partners for hints of corruption or ethical shadiness. President Donald Trump has said the law is “horrible.” Perhaps that’s because if he were a foreign official or businessman, American companies would think twice about working with him.

info@anticorr.media

info@anticorr.media