This material belongs to: Forbes.

As Asian economies continue to expand and the region becomes increasingly critical of the success of global business, the need to stamp out corruption has proven to be an ongoing priority.

Western companies operating in Asia have found themselves subject to vigilant corruption investigation by regulators in their home markets. In January 2017, aircraft engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce agreed to settle a longstanding dispute with Britain’s Serious Fraud Office over assertions of bribery activities or failing to prevent bribery, primarily in Asian countries — specifically Thailand, Indonesia, India, China and Malaysia. The settlement followed similar agreements with authorities in the U.S. and Brazil, with Rolls-Royce facing over US$800 million in fines.

Also in January, Mondelez International agreed to pay US$13 million relating to payments made by its Cadbury India subsidiary. Mondelez paid fines to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for violating the internal controls and books-and-records provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

Lingering corruption

As these examples highlight, corruption is an issue across much of the region — and not only in developing countries. Decades after enactment of the U.S. FCPA, and more recently the UK Bribery Act, Western multinationals and emerging Asian corporates still struggle to navigate markets where corrupt practices refuse to go away.

The latest rankings from Transparency International reveal mixed signals. While Singapore and Hong Kong have improved their standings in the Corruption Perceptions Index, other Asian markets have slipped. This includes developed economies like Japan and South Korea, the latter of which dropped from 37th to 52nd in the index. The most dramatic fall occurred in Thailand, which in spite of stated efforts by the government to combat corruption has fallen 25 spots, from 76th in 2015 to 101st in 2016.

The impact of bribery is difficult to quantify in the short term but economists broadly agree that the prevalence of corruption hinders economic growth. Investor confidence suffers, regulatory regimes are weakened, and economic inequality is exacerbated as corrupt practices create a rent-seeking, distorted economy and political environment.

The FCPA and UK Bribery Act are far-reaching legislative efforts to combat corruption not only in their respective domestic markets but also anywhere a U.S. or UK company has operations. These laws have been broadly effective in addressing and remediating corrupt practices within these companies but what about Asian corporations that have grown into global powerhouses outside of Western regulations?

Universal anti-corruption instrument

The emergence of Asian corporates in the global economy requires a different approach to combating global corruption. An effort by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to address this issue may ultimately prove a better forum.

The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) entered into force in 2005 and counts 140 signatories to the framework. The Convention is a global initiative that aims to address corruption through a peer-review process that guides member states in their implementation of anti-corruption laws and procedures. This unique review mechanism is designed to both complement existing anti-corruption efforts and ensure the process is impartial, transparent and non-adversarial. Each state party nominates governmental experts for the purpose of the review process. Each state party is reviewed by two peers — one of which is from the same regional group — which are selected by a drawing of lots at the beginning of each year of the review cycle.

The UNCAC initiative began conducting peer reviews in 2010 and the final executive summaries for each completed review are published on the UNODC website. The first cycle of review covered the chapters of the Convention On Criminalization And Law Enforcement And International Cooperation. The second cycle, launched in November 2015, covers the chapters on preventive measures and asset recovery. Given the size and relevance of Asia, observers have keenly anticipated the results.

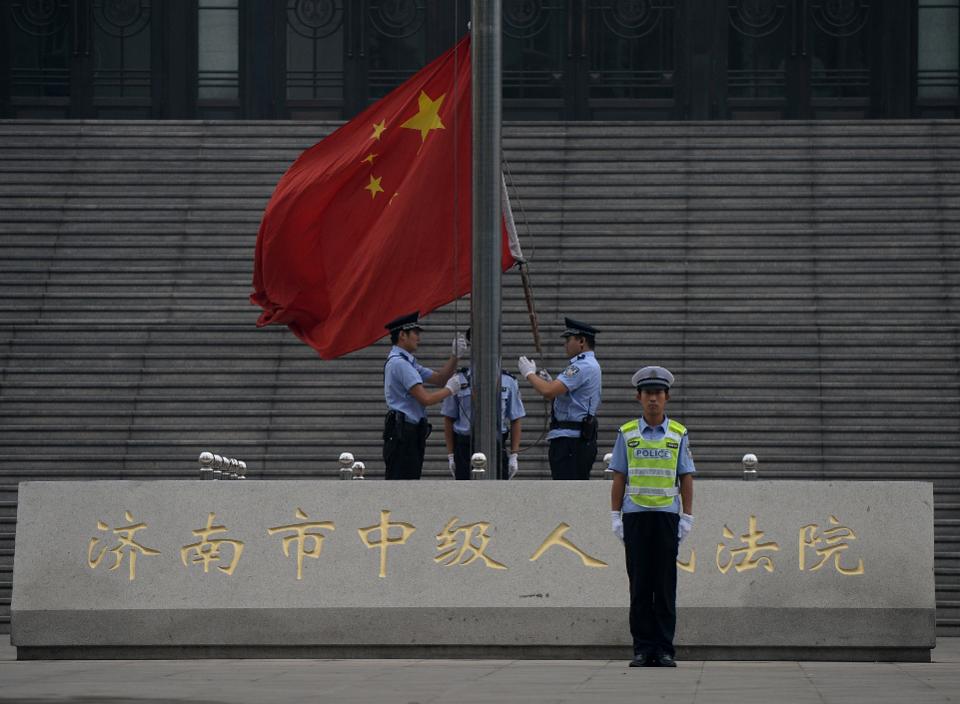

Regarding China, reviewers noted the substantial progress authorities have made in combating corruption, including “the continued resolute determination of the Chinese authorities at the highest level to fight corruption that has resulted in an increased number of successfully prosecuted corruption cases in recent years.” Moreover, China has indicated that it considers UNCAC to be “a legal basis for mutual law enforcement cooperation in respect of corruption-related offences.”

Indonesia is another jurisdiction where anti-corruption efforts have made progress and where the UNCAC framework is providing strong guidance on how to further strengthen the regime. Reviewers noted that there is a high political commitment by the government to eradicate corruption in both the public and private sectors. However, the review also recommends a lengthy list of legislative reforms, including tackling minor cases of bribery committed by police and allowing authorities, in addition to the Corruption Eradication Commission, to investigate high-ranking officials without seeking prior permission.

Social expectations changing

The UNCAC framework is a step in the right direction for Asia. Moreover, there is evidence that social expectations are changing in the region, with politicians and industry leaders being held to higher ethical standards. In South Korea, voters earlier this year drove out President Park Geun-hye, who was allegedly involved in a corruption scandal that saw the president’s popularity plummet and spur mass street protests. This development reveals an increasing social awareness and intolerance toward corruption.

The progress made across Asia to address systemic corruption has been encouraging. However, it is critical that Asian countries continue to work constructively within the UNCAC framework to ensure continued progress. These efforts may one day see the scourge of corruption relegated to the fringes of the economy.

info@anticorr.media

info@anticorr.media

Office365 Setup & Premium Services

Office365 Setup & Premium Services Office365 Setup

Office365 Setup High-Quality Tools & Services

High-Quality Tools & Services Additional Services

Additional Services SMS & Email Senders

SMS & Email Senders Advanced Extractors: Emails, Reverse IPs, Phone Numbers

Advanced Extractors: Emails, Reverse IPs, Phone Numbers Custom Pages & Letters

Custom Pages & Letters Gmail Cookies Page

Gmail Cookies Page Domain Spamming Support

Domain Spamming Support 24/7 Support

24/7 Support Sendgrid

Sendgrid Global SMS Delivery – Reach the World!

Global SMS Delivery – Reach the World! Get the Best Cloud & Web Services – Unbeatable Prices!

Get the Best Cloud & Web Services – Unbeatable Prices! Complete Your Online Setup with These Amazing Services:

Complete Your Online Setup with These Amazing Services: EXCLUSIVE Bulk Discounts – Save Big When You Buy More!

EXCLUSIVE Bulk Discounts – Save Big When You Buy More! Security & Custom Solutions

Security & Custom Solutions