This material belongs to: The Washington Post.

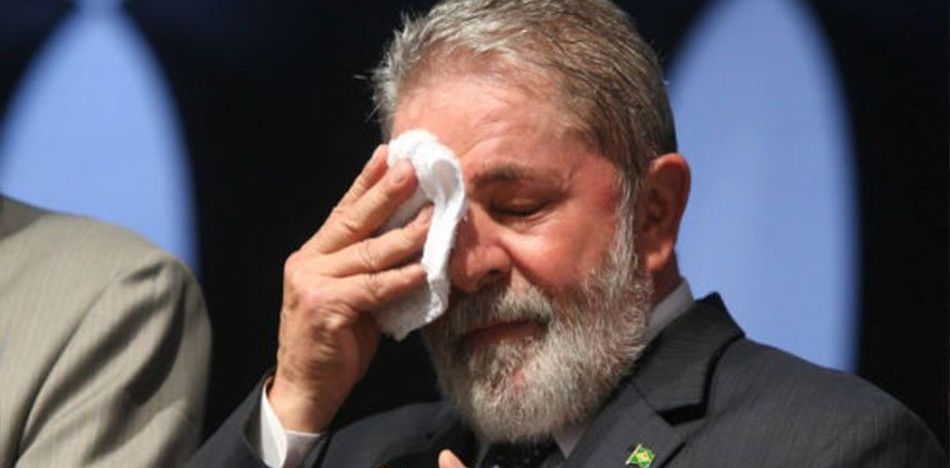

PORTO ALEGRE, Brazil — An appeals court panel on Wednesday unanimously upheld a corruption conviction against former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a ruling that upends this nation’s presidential race and complicates the political comeback of one of Latin America’s best-known figures.

The justices indicated they would stop short of the politically charged step of jailing the leftist icon as he continues his legal fight. But for the 72-year-old known simply as “Lula,” the 3-0 ruling poses potentially career-ending obstacles.

Brazil’s poverty-busting president from 2003 to 2011 has emerged as the early front-runner in this year’s presidential race. He is the left’s best chance against a field of candidates including his closest rival, a far-right firebrand known for misogynistic comments. But Brazil’s “clean record law” bars politicians with convictions upheld on appeal from running for office.

“There is proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the ex-president was one of the actors, if not the principal actor, of an ample corruption scheme,” one of the appellate judges, João Pedro Gebran Neto, said in the courtroom. He recommended that Lula’s 2017 sentence of 9 1/2 years be extended to more than 12 years, saying that “at a minimum, he was conscious and gave support to what happened.”

A defiant Lula proclaimed his innocence after the ruling and promised to fight on. “No heads down. Heads high. . . . Never give up,” he told supporters in Sao Paulo. “I want to warn the Brazilian elite: Just wait because we will be back,” he added.

“I don’t want anyone to be worried for Lula,” the former president said. “I want us to be worried about what is happening in government.”

Linked to a massive corruption probe known as “Operation Car Wash,” Lula was convicted of receiving bribes worth more than $1 million, mostly in the form of a refurbished beachfront apartment. He can still appeal to higher courts. But Wednesday’s outcome suggested a protracted legal battle ahead in which Lula’s eligibility to run might not be fully determined until as late as September — a month before the elections.

Higher courts have been generally upholding convictions linked to Car Wash, a four-year probe into bribes paid by construction companies to public officials in exchange for lucrative government contracts, many with the state-owned oil company.

But Lula’s Workers’ Party has pledged to stick by his candidacy no matter what. His ardent supporters immediately denounced the decision as a politically motivated gambit and burned tires on streets here and in Sao Paulo, Brazil’s largest city.

His backers built a small tent city here ahead of the verdict, complete with makeshift stores and restaurants. Earlier Wednesday, they marched as close as they could get to the courthouse, but huge lines of police officers on horseback held them back. After the decision, and amid a driving rain in Porto Alegre, dejected supporters packed buses en route to their homes.

“I’m frustrated and sad, but the fight is much bigger than this,” said Ronaldo Soares, 41, a trainee chef who traveled 3½ days by bus to rally for Lula. “A new dictatorship is starting in Brazil. It’s a class fight. The rich and elite, the market forces, big business is in charge of everything. This is a big step back for the workers, but we need to step up and fight for Lula because he represents democracy.”

Demonstrators against Lula, meanwhile, celebrated in the streets, hailing the verdict as a sign that the rule of law was being upheld.

“All the mechanisms to guarantee impunity in public officials were put in place to try and protect Lula,” said Iria Cabrera, organizer of an anti-Lula demonstration in Porto Alegre. “And if this person can see justice, you open a path to have people pay for their crimes, any person on any level.”

Lula’s 2017 conviction stems from allegations he accepted the remodeled beachfront pad in a middle-class resort from a construction firm in return for public contracts. Wednesday’s unanimous decision leaves Lula with two remaining appeals, including to Brazil’s supreme court. However, Lula can also apply to an electoral tribunal for a special exemption to run for president despite the conviction if his appeal drags on.

“One thing that could play to Lula’s advantage is that political considerations are likely to play an increasingly important role in the process,” said Peter Hakim, a senior fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue. “To be sure, the decisions will, for the most part, be made by mostly honest and competent judges. But, like judges in the U.S., they do have political views that affect their reasoning.”

The decision will shape the 2018 presidential race in a nation exhausted by nonstop political scandals.

In October, Brazilian lawmakers blocked a corruption trial against President Michel Temer after concessions to pro-business political factions. Temer took office in 2016 after President Dilma Rousseff was impeached for fiscal abuses. But Temer remains hugely unpopular, with approval ratings as low as 3 percent.

If Lula is unable to run, it could present an opening for the right — including former army officer Jair Bolsonaro, his leading rival, or Sao Paulo Mayor João Doria, a businessman turned host of Brazil’s version of “The Apprentice” who has been widely compared to the show’s former American host, President Trump.

Lula’s “base sees him as a godlike figure,” said Heni Ozi Cukier, a political scientist at ESPM University, also in Sao Paulo. “If Lula is in the election, the election becomes about who can beat Lula. Without Lula, it’s a very open playing field.”

The conviction has amounted to a hard fall from grace for a man who once ranked as Brazil’s best-liked president and who was described by former U.S. president Barack Obama as “the most popular politician on Earth.” He was the nation’s first leader from a poor background — a factory worker who made his way into politics by way of prominent labor unions.

Under his leadership, Brazil’s economy boomed, and 40 million people rose out of poverty as he built an ambitious social safety net called “zero hunger.”

Yet Lula is accused of seven other crimes — including other counts of corruption, influence peddling and illegal campaign financing.

In addition to the beach apartment in the resort of Guaruja, prosecutors say he received an apartment on the outskirts of Sao Paulo and a $4 million plot of land where his charitable institute is located.

Lula and his allies maintain that the charges are all politically motivated. His defense team says he and his wife, Marisa, never owned the beachfront apartment in question and visited the unit only to consider purchasing it.

“This process has been marked by gross violations of due process,” one of Lula’s lawyers, Cristiano Zanin Martins, said this week. “The prosecutors have utilized the press and social networks to try to demonize Lula and try to impede his right to be innocent until proven guilty.”

Yet on Wednesday, the appeals court said witness testimony indicated that the apartment in question had been reserved for Lula and his wife and that renovations on it were made at his request. The court took issue with the defense team’s insistence that the judges were acting as the political puppets of Lula’s right-wing opponents.

“Just like what happened with American President Richard Nixon in the Watergate case . . . we now see [that] the law is for everyone,” said Justice Leonardo Paulsen.