This material belongs to: NY Times.

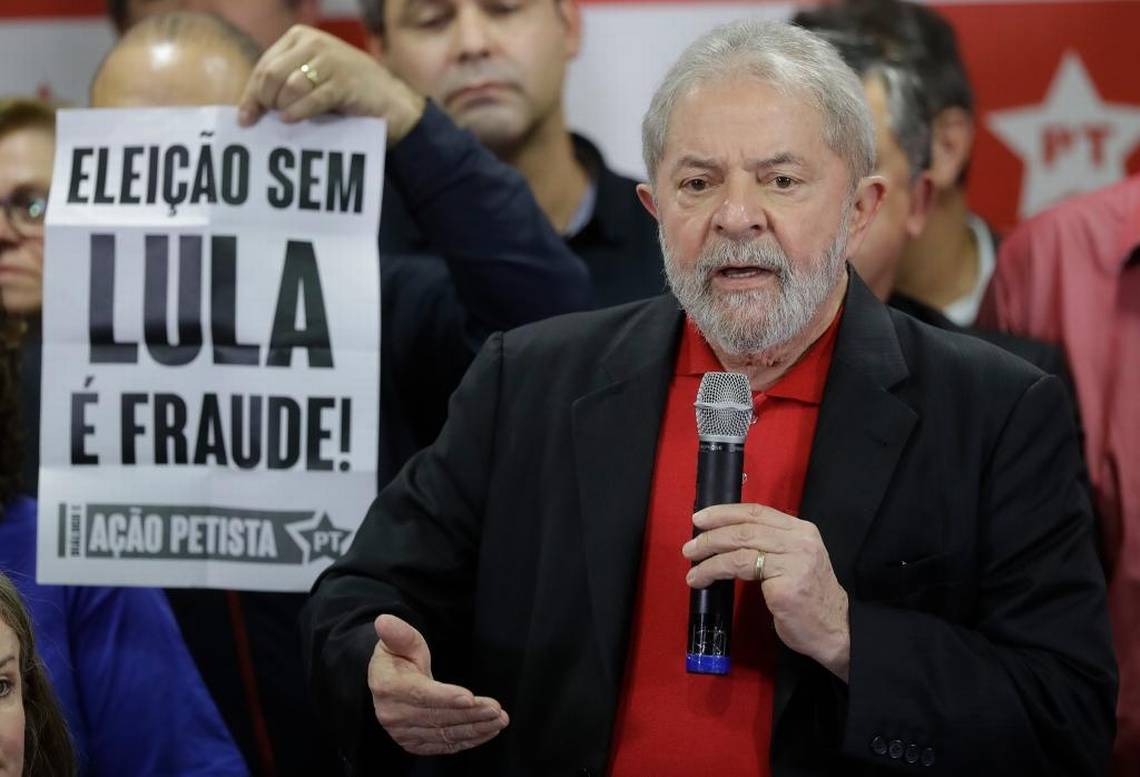

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Brazil’s attorney general on Tuesday charged former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva; his successor, Dilma Rousseff; and several other senior figures of the Workers’ Party with running a “criminal organization” that raked in hundreds of millions in bribes during the party’s nearly 14-year reign.

The case is the first in which Ms. Rousseff, who was impeached last year for violating budgetary rules, stands accused of partaking in the kickback schemes that have cast a pall over every major Brazilian political party.

The charges were unveiled the same day that Mr. da Silva wrapped up a 25-city campaign trip through his party’s strongholds in the northeast, during which he sought to play down a recent corruption conviction that may doom his ambition to return to the presidency.

The attorney general, Rodrigo Janot, whose term ends this month, described the governments of Mr. da Silva and Ms. Rousseff as essentially fronts for a criminal enterprise through which senior politicians collected roughly $450 million from entities that included the state-run oil company Petrobras and the Brazilian National Development Bank. In addition to his conviction, Mr. da Silva has been charged in several other cases in which he stands accused of accepting bribes of relatively modest sums.

But the 230-page charge sheet released Tuesday puts him at the center of a huge conspiracy. Mr. Janot wrote that the allegations should not be seen as a sign that the judiciary was “criminalizing politics” or routine “political negotiations,” but rather as a record of a ruling elite that systematically used public money to “buy popular support.”

The accusations against Ms. Rousseff, who has portrayed herself as a clean politician who was brought down by a cabal of corrupt rivals, is a startling development in the series of revelations that spun from a routine investigation of money laundering at a gas station in Brasília, Brazil’s capital, in 2014.

“This is very significant,” said Matthew M. Taylor, a professor at American University in Washington who studies Brazil’s justice system. “Dilma had been arguing that she was personally honest.”

Mr. Janot described Mr. da Silva as the mastermind of the kickback scheme, initially as president and later as a result of the “strong influence he exercised over” Ms. Rousseff. The attorney general emphasized that many key players in the bribery scheme were supported or appointed by Ms. Rousseff.

“Dilma Rousseff integrated the current criminal organization since 2003 when she accepted” Mr. da Silva’s invitation to run the Ministry of Mines and Energy, he wrote. “From there, she contributed decisively so that the private interests negotiated in exchange for bribes could be met, especially in relation to Petrobras, where she was the president of the board between 2003 and 2010.”

Mr. Janot, who was appointed by Ms. Rousseff in 2013, wrote that Mr. da Silva and Ms. Rousseff spread the wealth, inviting leaders of other political parties to take part in the scheme.

“Critics had long said that given her prominent roles on the Petrobras board, and as head of the M.M.E., Dilma was either complicit or incompetent,” Mr. Taylor said. “Janot clearly thinks the former.”

But in a statement released Tuesday night, Ms. Rousseff’s press office said, “Without presenting proof or evidence of a material crime, the attorney general’s office is filing charges without any foundation whatsoever.”

And the Workers’ Party, in its own statement, called the allegations baseless and the continuation of a vendetta by the judiciary to weaken certain political factions through “selective persecution.”

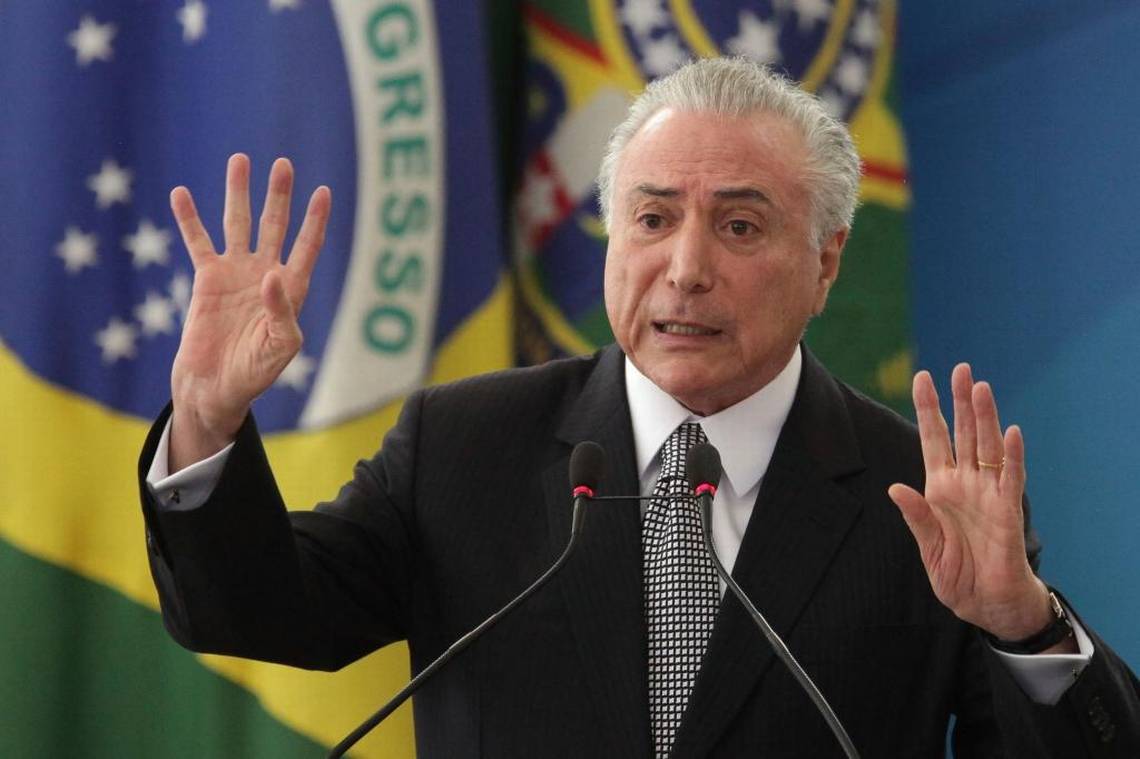

The case was filed as President Michel Temer, who stepped into the job after Ms. Rousseff’s impeachment in August 2016, was himself bracing for a new set of corruption charges. Mr. Janot charged Mr. Temer with corruption in June over accusations that he authorized a bribe to keep an imprisoned politician silent. The president managed to avoid standing trial in that case by getting enough members of the lower house of Congress to block the case from reaching the Supreme Court — the only court where senior Brazilian elected officials may be tried.

One defendant in the latest case, Senator Gleisi Hoffmann, who took the helm of the Workers’ Party in June, enjoys the same legal protection, which critics say has contributed to a culture of impunity among Brazilian politicians.

It was unclear whether the case caught the defendants by surprise. As Brazilians were poring through the charging document, Mr. da Silva was sounding triumphant at the end of his caravan tour.

“I’ll say one thing: we’re going to govern this country again,” he said in a post on Twitter addressing his followers. “And when I saw we, it’s not me. It’s you.”

Also charged in the case were: Guido Mantega, a former finance minister; Paulo Bernardo, a former communications minister; Antonio Palocci Filho, a former chief of staff for Ms. Rousseff; João Vaccari Neto, a former treasurer for the Workers’ Party; and Edinho Silva, the mayor of Araraquara.

Brazil engulfed in a corruption scandal with plots as convoluted as a telenovela

This material belongs to: Miami Herald.

RIO DE JANEIRO

For more than three years Brazilians have been following the almost daily headlines of a corruption investigation that takes its name, Operation Lava Jato (Car Wash), from a Brasilia gas station where illicit gains were being laundered through a money exchange service.

But the investigation, which began on May 17, 2014, has now moved far beyond money-laundering to probe corruption at the state-controlled oil company Petrobras and bribes paid by some of the biggest companies in Brazil to politicians at the highest level of government.

Operation Lava Jata has included more twists and turns than a Brazilian soap opera and has come dangerously close to sitting President Michel Temer. In early August, Brazil’s lower House of Deputies voted not to forward a corruption case against Temer to the Supreme Court for trial but prosecutors say other charges against the president may be forthcoming.

Temer spent a lot of political capital in his victory, including freeing up money for pet projects in legislators’ home districts, and his struggle to defend himself could distract from his legislative agenda and critical pension reform needed to balance Brazil’s books and avert a fiscal crisis.

If Rodrigo Janot, the chief federal prosecutor, does decide to file other charges against Temer, the lower house would once again decide whether the case should be sent to the Supreme Court.

So far there has been enough drama in the Lava Jato investigation to rival any Brazilian telenovela. Among the highlights: stings, a secret recording of the president made by a tainted businessman, a mysterious plane crash, Swiss bank accounts, hush money, tracking chips in bags of cash, and a robbery/shooting that sent a bag full of alleged bribe money floating over a Rio square.

The investigation, spearheaded by Federal Judge Sérgio Moro, has snared former presidents and billionaire corporate chieftains in a scheme where bribes were paid to win contracts at inflated prices and other favors were exchanged. Illegal payments of more than $5 billion were allegedly made, and the investigation is far from over.

Lava Jato also has spawned many offshoot investigations and has moved well beyond the borders of Brazil to at least 12 countries where Brazilian companies are accused of paying bribes to win contracts and influence people.

The break that turned Lava Jato from an investigation of money laundering through a Brasilia gas station/car wash into a massive corruption investigation came when prosecutors were able to connect Alberto Youssef, a black market money dealer, or doleiro, with Paulo Roberto Costa, a former director of Petrobras, the state-controlled oil company.

Both entered into plea bargains, and Costa told investigators that Petrobras overpaid on everything from construction contracts to oil refineries and drilling rigs. In exchange for guaranteed contracts, he said, companies that worked with Petrobras agreed to padded contracts.

A gusher of bribes aimed at keeping incumbent politicians in power was paid out in cash, luxury cars and other trappings of the good life, according to investigators.

Soon the Lava Jato investigation began to expand in ever widening circles that also focused on Brazil’s nine major construction companies, JBS — one of the world’s largest meat packing firms, public contracts and the politicians alleged to have profited from the bribes.

Odebrecht, a global conglomerate with interests not only in construction and engineering but oil and gas, logistics and bioenergy and power generation, was an early Lava Jato target. In December, Odebrecht and Braskem — a petrochemical company controlled by Odebrecht — pleaded guilty to paying $788 million in bribes to corrupt government officials and politicians around the world to secure contracts. The companies agreed to pay $3.5 billion to settle charges by authorities in the United States, Brazil, and Switzerland.

Odebrecht used the global financial system, including the U.S. banking system, to disguise the source and payment of the bribes by passing them through shell companies.

Marcelo Odebrecht, chief executive of Odebrecht and grandson of the firm’s founder, was arrested in 2015, convicted of paying more than $30 million in bribes to Petrobras executives and sentenced to 19 years. Odebrecht’s lawyers are currently trying to get his jail time reduced and he could be released before Christmas 2018. Nearly 80 other Odebrecht executives have agreed to plea bargains and are under house arrest.

But analysts say the big fish at this point aren’t the business executives, but rather the politicians who, up to now, have largely escaped prosecution.

“We seemed to be releasing the sharks. They are at home with their ankle monitors,” said Iuri Dantas, an editor at JOTA.info, a Brazilian news website that focuses on the judiciary. “But then recently we’ve begun to understand the sharks are really the politicians.”

More than 100 politicians have been charged in Operation Car Wash so far, but only a few are serving jail terms.

The biggest fish so far is former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who left office in 2011. He was convicted of corruption in July and sentenced to 9 1/2 years in prison but is appealing the conviction and hasn’t served any jail time.

His supporters are hoping his appeal will be successful so that he can run in the 2018 presidential election but more charges related to $1.2 million in bribes he allegedly accepted also are possible.

Another former president, Fernando Collor, also faces trial on charges of corruption, money laundering, and running a criminal organization for allegedly taking bribes to help firms win contracts with BR Distribuidora, Petrobras’ fuel distribution unit. Some of the money he received was allegedly laundered through the acquisition of luxury cars, artwork, and a boat.

Lava Jato has built momentum on the testimony of informants and an avalanche of plea bargains as those caught in the net of justice sing.

Wealthy executives rarely spent even minimum time in jail in the past, but this time prosecutors have often denied them bail and used preventive detention to hold them. They have found it in their interest to cooperate and serve out sentences under house arrest after implicating others — rather than facing the cold reality of jail.

Plea bargaining is a relatively new tool for Brazilian prosecutors. Instituting plea bargaining was one of the new laws and tools aimed at rooting out corruption that were fast-tracked during the administration of former President Dilma Rousseff, who had zero tolerance for corruption.

She herself was impeached for false accounting by shifting money between accounts to make government finances appear in better shape — not as part of the Lava Jato investigation — but other presidents have done as much without similar consequences.

Rousseff had other problems. Her economic policies were unpopular and she was blamed for Brazil’s recession, but beyond that, some analysts believe her anti-corruption stance also contributed to her ouster last August.

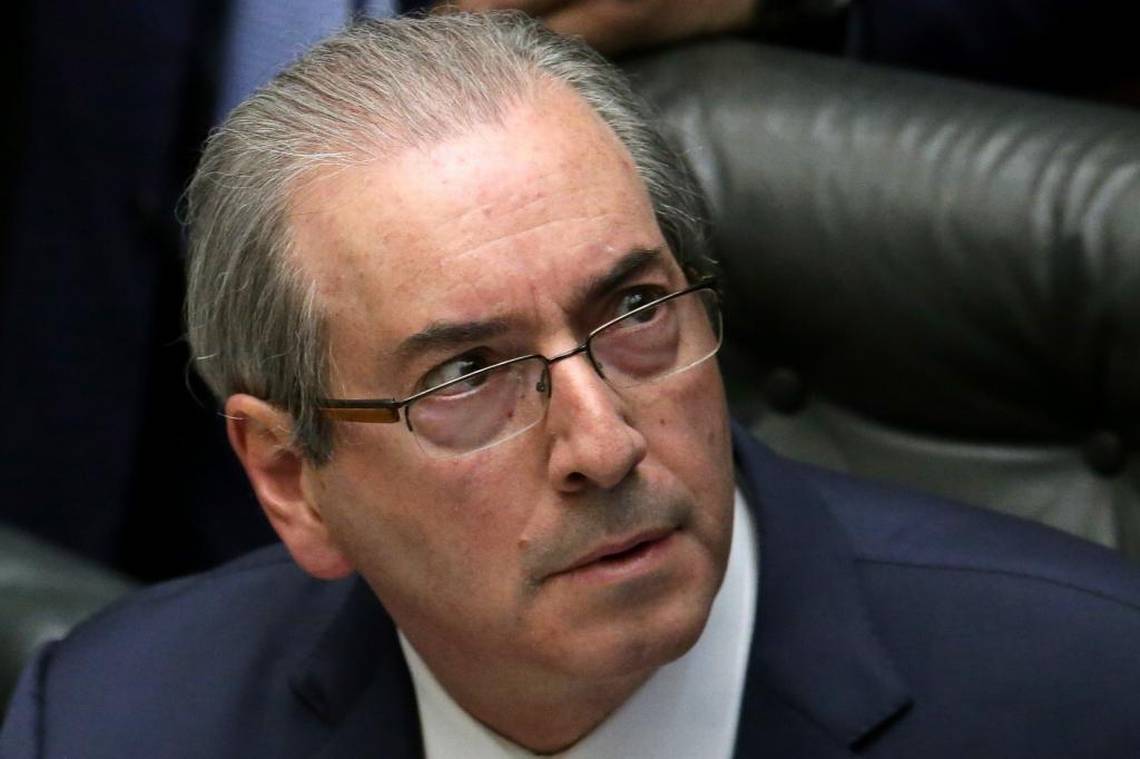

She did little to protect high-ranking members of her ruling coalition from corruption accusations, and the bid to oust her was orchestrated by Eduardo Cunha, former speaker of the House of Deputies who in March was sentenced to 15 years in prison on money laundering, corruption and currency law evasion. The charges against him stemmed from a $1.6 million bribe prosecutors say he received from Petrobras.

In recent weeks, Rousseff, who says Lula’s conviction is a “mockery,” has appeared with him at political rallies focused on his return to the presidency in 2018.

Brazilians, meanwhile, need a scorecard to keep track of who has been convicted, accused and taken prisoner, and the Lava Jato investigation has provided the nation with plenty of scandals — too much some would say.

On Jan. 19, a small plane carrying Brazilian Supreme Court Justice Teori Zavascki, who had been handling the Lava Jato trials, crashed into the sea near Paraty. He and four others aboard died. The weather was stormy, but investigators said the plane did not appear to have any mechanical problems.

Also shocking to Brazilians was the late-night visit to Temer’s official residence by Joesley Batista, one of three brothers that ran JBS, one of the world’s biggest meat packing companies and himself a Lava Jato target.

Although Temer has denied that he has had anything to do with bribes, Batista was carrying a recording device during his March visit. Their recorded conversation appeared to indicate that the president may have been condoning the payment of hush money to Cunha. Temer has denied he ever solicited money to buy Cunha’s silence.

The secret recording led to a videotaped sting operation that shows a Batista associate handing over a suitcase full of cash to Rodrigo Rocha Loures, a trusted Temer associate, who is shown running across the parking lot of a pizza parlor carrying the suitcase containing more than $150,000 in cash.

In the interest of transparency, prosecutors have released both the taped conversation with the president and the video, which has been played over and over on Brazilian television.

Batista and his brother Wesley have turned over documents to prosecutors that detail alleged payments to 1,829 politicians from 28 parties through official donations, illegal campaign contributions or through bribes in exchange for favorable treatment for their businesses.

For his cooperation, Joesley Batista has escaped both jail time and the requirement to wear an electronic ankle bracelet.

“Today Brazil is undergoing three crises: one of ethics, one of politics and one of economics,” said Janot, the chief prosecutor during a trip to Washington in July. It’s common to attribute them all to the biggest criminal investigation in Latin America, but he said Lava Jato isn’t to blame, but rather a corrupt system under which certain companies found a way to impede competition and maintain themselves through bribery.

“We hear everyday that the Brazilian justice system is criminalizing politics,” said Janot, whose term is scheduled to end Sept. 17. “This is not true. What we do is apply criminal law and look for criminals — even those who have political mandates.”

While polls show that most Brazilians support the assault on corruption, they didn’t take to the streets in massive numbers to express dismay at Temer’s dodging trial as they did in 2013 when millions of Brazilians were in the streets protesting everything from rising bus fares to corruption and the lack of quality healthcare and public education.

One reason may be that unlike Rousseff’s, Temer’s economic agenda isn’t reviled. But a certain Lava Jato fatigue also has begun to set in. Journalists say the charges against the high and mighty have become so routine that readership of such stories is down and people aren’t commenting on them as much online.

“I think right now people are tired,” said Natalia Viana, of Publica, a Rio-based investigative journalism agency. “Brazilians have been very accustomed to corruption in political life. But unlike before, something did happen — people were removed from office. There was hope that the investigation might cause permanent change in Brazil, but now with Temer getting off, people are starting to lose that hope,” she said. “We are in a chess game, but we are three steps behind.”

“I think the turning point will be in the hands of Brazilian society that is already saturated with this,” said Alana Rizzo, a director of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism.

Now investigative task forces have begun to probe new areas, including contracts related to construction for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Rio Olympics.

“I expect this could go on for the next five years — at least,” said Dantas.

Janot said his greatest disappointment as prosecutor is that the investigation didn’t move as fast as he would have liked. But he said it’s necessary for the spotlight to continue to shine on corruption to cleanse everything in Brazil.

As the investigation grinds on, Janot said it’s important to remember that a corrupt system steals from public education, healthcare and public safety budgets. But most of all, he said, “corruption steals the hope and future of a people.”