This material belongs to: The Washington Post.

LIMA, Peru — He took office in 2016 as a political outsider boasting that his strong business credentials would buoy Peru’s economy while sweeping away endemic corruption. But with his offer of resignation, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski joins a long list of recent Peruvian presidents undone by scandals that have destroyed voters’ trust in their elected officials.

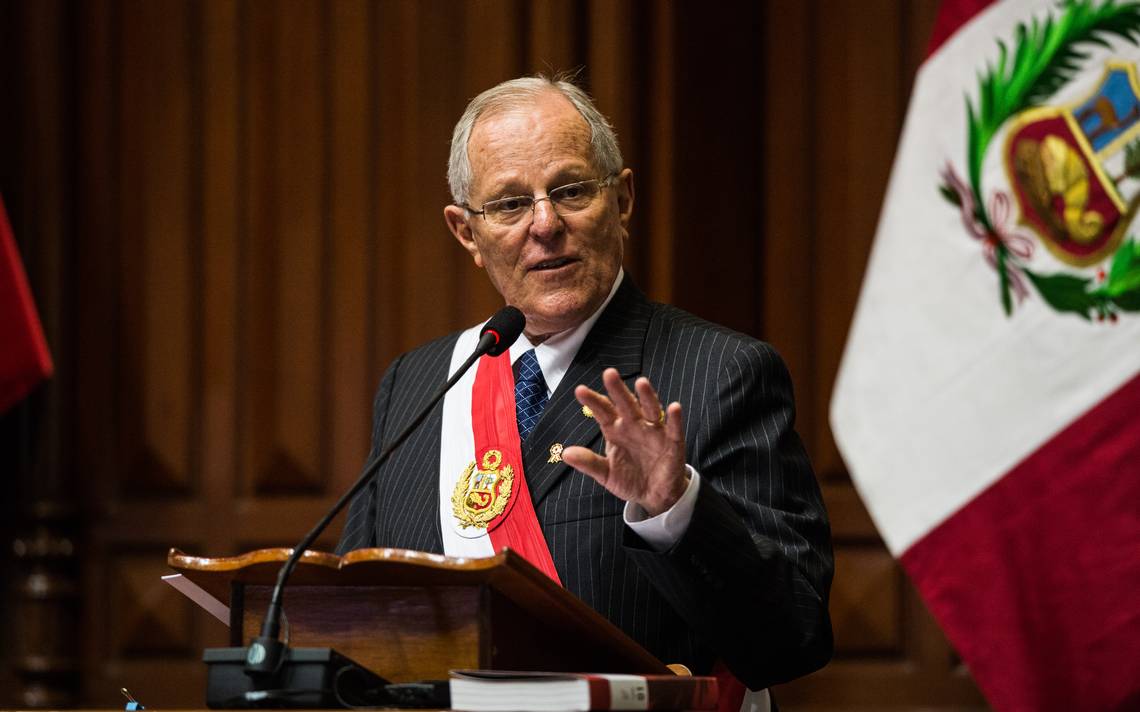

Kuczynski, flanked by his cabinet, announced his decision to resign Wednesday in a nationally televised address, accusing opponents led by the daughter of former strongman Alberto Fujimori of plotting his overthrow for months and making it impossible to govern.

Shortly after, he exited the back door of the baroque presidential palace built by Spanish conquerors and was driven off, all alone, in an SUV.

Congress was expected to vote Thursday to accept his resignation, or if not, to impeach him.

It was an ignominious end to a presidency that started with the highest of expectations.

When Kuczynski, a former Wall Street investor, was elected in 2016, he was immediately thrust to the helm of a conservative revival in South America. Voters had grown tired of once-dominant leftist governments marred by corruption and blamed for squandering a decade-long commodities boom that had ended abruptly.

At home, he promised an investment windfall from old business buddies in the U.S., where he lived for decades and met his current and former American wives. He also surprised many by speaking out forcefully against Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro and leading a coalition of like-minded leaders to isolate the socialist leader for human rights abuses.

But the 79-year-old was hobbled almost immediately out of the gate. His self-tailored party, named for his own PPK initials, won just 18 seats in the 130-member congress. And instead of courting supporters on the left who pushed him to victory by a razor-thin margin over opponent Keiko Fujimori, he tried in vain to form an alliance with the former strongman’s power-hungry, vindictive allies. Aides privately complained of stubbornness and political naiveté.

“When Kuczynski came in, everyone hailed him as Peru’s salvation,” said Laura Sharkey, a Bogota-based analyst at Control Risks consultancy. “But he just completely underestimated the strength of the opposition.”

Even on the economy, his strong suit, Kuczynski fell short, as growth has slowed and promised mining and infrastructure projects never got off the ground.

What most outraged voters, however, was his seeming dishonesty, something that has long dominated Peruvian politics and he had vowed to end.

For months, as three of his predecessors were probed and one even jailed for taking bribes from Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht, Kuczynski steadfastly denied having any business or political ties with the company at the heart of Latin America’s biggest graft scandal.

Then, Fujimori’s party produced confidential bank documents from Odebrecht showing $780,000 in decade-old payments to his consulting firm. Kuczynski said he had no knowledge of the payments that overlapped with his years as a government minister and said that in any case had paid taxes on all of his earnings.

To save his skin he cut the sort of closed-door deal that Peruvians have grown to abhor. A group of lawmakers led by Kenji Fujimori defied his sister’s leadership of the Popular Force party to narrowly block Kuczynski’s impeachment. Days later, Kuczynski pardoned the feuding siblings’ father from a 25-year jail sentence for human rights abuses committed during his decade-long presidency.

Ultimately that alliance spelled his downfall. Popular Force this week revealed secretly shot videos of Kenji Fujimori and other presidential allies allegedly trying to buy the support of an opposition lawmaker with promises of state contracts.

Kuczynski denied any bribery attempt, but for Peruvians traumatised by the videos of Fujimori’s longtime spy chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, handing out huge stacks of bills to politicians, military officers and media moguls, the damage was done.

To be sure, Keiko Fujimori seems unlikely to be able to fill the void. An Ipsos poll taken this month showed that while a dismal 19 percent of Peruvians approve of Kuczynski’s presidency an even smaller number, 14 percent, have a favorable view of congress, where Fujimori’s party is dominant. The poll had a margin of error of 2.8 percentage points.

In addition to the bitter feud with her brother, Fujimori herself is facing accusations that her own 2011 presidential campaign received never-declared contributions from Odebrecht, something she denies.

For many Peruvians, the clandestine videos that did Kuczynski in are a reminder of the corrupt, deceit-filled politics of the Fujimori era that they had hoped was behind them. In the coming days, as Peru works its way through a messy presidential succession, that widespread outrage is likely to fuel louder calls for early elections — for both congress and the presidency.

“The only public institution with moral authority left in Peru is the fire department,” said Oscar Mendoza, a lawyer standing outside the presidential palace moments after Kuczynski waved goodbye to aides. “All the rest, when you touch them with your finger, puss comes out because they are fully corrupted by graft.”