This material belongs to: The Nation.

Warning sounded as nationwide scandal at destitute centres implicates dozens.

THE RECENT corruption scandal involving state-run protection centres for the destitute has revealed a worrying form of graft that is much harder to investigate, an anti-corruption watchdog has said.

This was because the alleged corruption – where money meant for the poor was allegedly diverted to state officials – occurred in many regions, and there were many potential suspects and witnesses, said Mana Nimitmongkol, secretary general of the Anti-Corruption Organisation of Thailand.

“A gigantic number of files for investigation are in the hands of junior officials across the country,” he said. “Information used to back the investigation will also have to come from grassroots people. How many of them will dare to speak up?”

He said in the past large-scale corruption usually involved just a handful of top officials at central agencies, which was easier to investigate.

The Office of the Public-Sector Anti-Corruption Commission (PACC) is investigating 37 provincial protection centres for the destitute, each of which had a budget of more than Bt1 million in the 2017 fiscal year to distribute to people in need.

The investigation began because of an unlikely whistle blower, a university student trainee at the Khon Kaen Protection Centre for the Destitute, who claimed that she had been forced to forge official forms.

The student, Panida Yotpanya, decided to speak up even though she was berated by a lecturer in whom she had confided.

Mana praised Panida for setting a good example for young people to follow. “She is an exemplary active citizen. She is the type of person we can place our hopes in. If there are many people like her, we will be able to eradicate corruption,” he said.

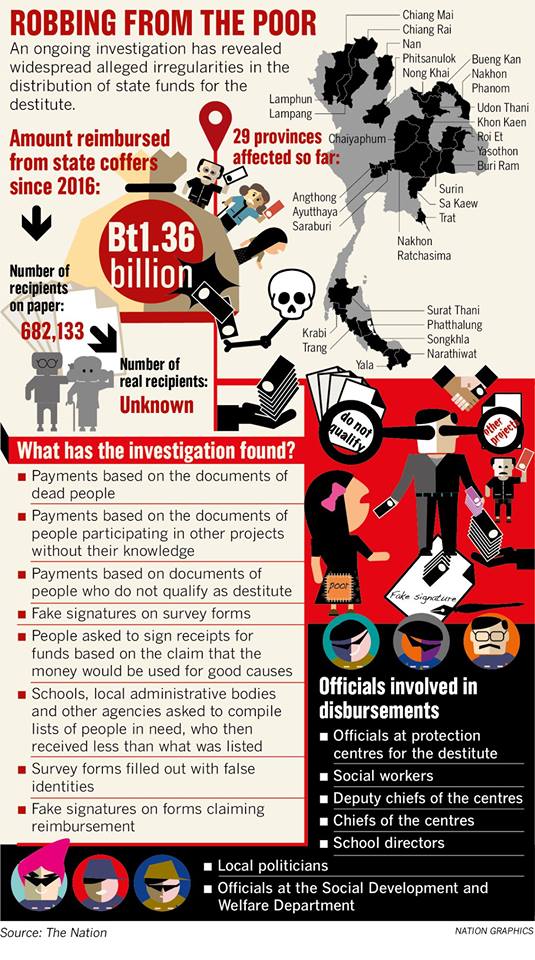

As of press time, the PACC probe had detected alleged irregularities in at least 29 provinces.

Mana said given the scale of the alleged graft, there was a high possibility that top officials were involved. In that case, the money was allocated to people at low levels first. The alleged corruption took place in the regions and kickbacks were allegedly sent to the higher levels, he said.

“It’s worrying because these alleged wrongdoers could learn from the cheating they got away with, then become confident and more prone to do it again and again,” he said.

Mana said the case seemed to involve systematic cheating, with lower-ranked and higher-ranked officials conspiring to help each other, while civilians were also pulled into the web. If people participated in such “irregularities” continuously, it would become a social value that could be described as a “win-win” situation despite its immorality.

If it was accepted at that level, no one would blow the whistle on wrongdoing and corruption would become more deeply rooted, he added.

Mana asked why officials Puttipat Lertchaowasit and Narong Kongkam had been promoted to the posts of permanent secretary and deputy permanent secretary respectively for Social Development and Human Security, even after the Office of the Auditor-General alerted the ministry in the middle of 2017 that they might have been engaged in corruption.

Although Puttipat and Narong have now been transferred out of the ministry, the transfers are not permanent.

“Given that they will still be able to wield influence at the ministry to an extent, I am worried that the investigation will be affected,” he said.

He said some senior officials’ attempts to paint the case as a “misunderstanding” also showed it might be difficult to investigate it or similar cases in the future.

“I’d like to ask if the authorities will do anything about this case as per the National Council for Peace and Order’s order number 69/2557, which says if a civil servant is caught committing corruption, his or her supervisor will be held responsible too,” he said.

Mana said the government should do more about the case, which had exposed alleged corruption in offices across half of the country, rather than just let the inquiry go on indefinitely.

Pisit Leelavachiropas, a former auditor-general, said the hope was that there would be enough evidence to identify the culprits, no matter how senior they were in rank. “It is possible to trace [the alleged corruption] through the line of command,” he said.

Pisit added that at the very least high-ranking officials could be held accountable for negligence given that alleged irregularities had spread over a wide area of the country.

Many forms of corruption had taken place in the country, he said.

“But no one had ever imagined before that officials would steal money designated for the destitute, such as those living with HIV,” he added.

Pisit said he hoped that the probe into the case would not end with just the 2017 fiscal year.

“Check deeper and backward so as to nail down all accomplices,” he added.

In a related development, PACC chief assistant Pol Lt-Colonel Wannop Somjintanakul said his team had on Friday found evidence of corruption related to the destitute fund at Nakhon Phanom’s Na Wa and Na Tom districts and would proceed with legal action against state officials and others allegedly involved.

He said the PACC aimed to complete its investigation into 37 provincial protection centres for the destitute by the end of March, and of the other 39 such centres by May.