This material belongs to: OCCRP.

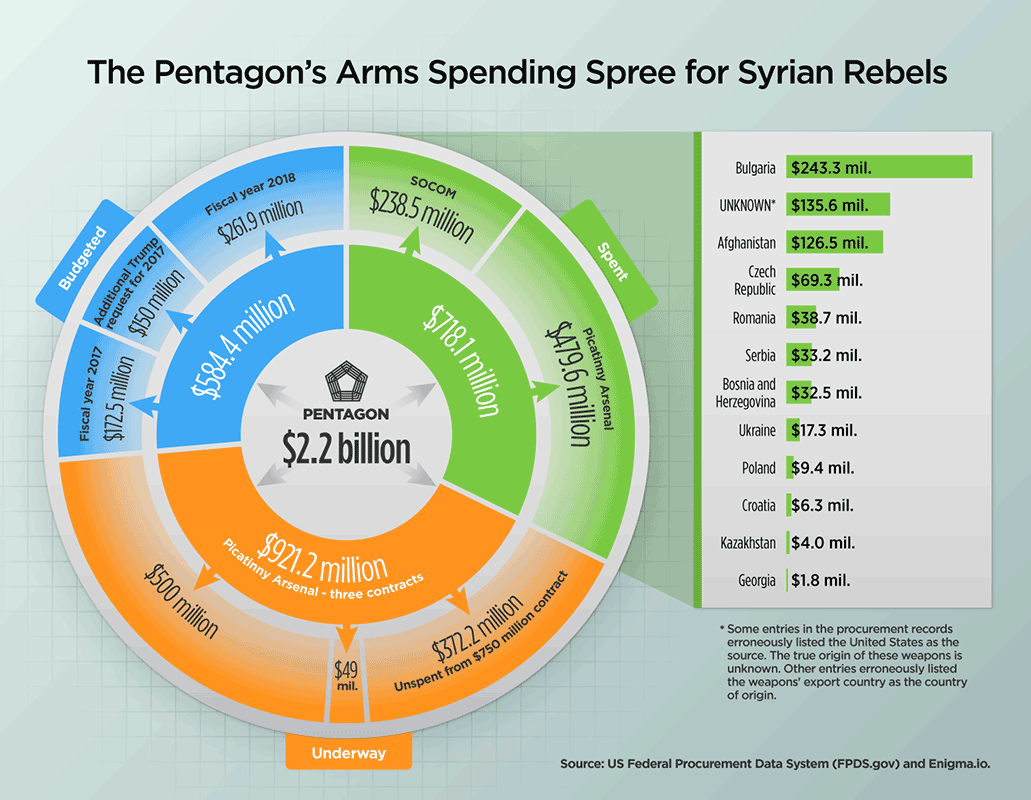

The Pentagon has relied on an army of contractors and sub-contractors – from blue-chip military giants to firms linked to organized crime – to supply up to US$ 2.2 billion worth of Soviet-style arms and ammunition to Syrian rebels fighting a sprawling war against the Islamic State (ISIS).

Arms factories across the Balkans and Eastern Europe – already working at capacity to supply the Syrian war – are unable to meet the demand. In response, the US Department of Defense (DoD) has turned to new suppliers like Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Ukraine for additional munitions while relaxing standards on the material it’s willing to accept, according to an investigation by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

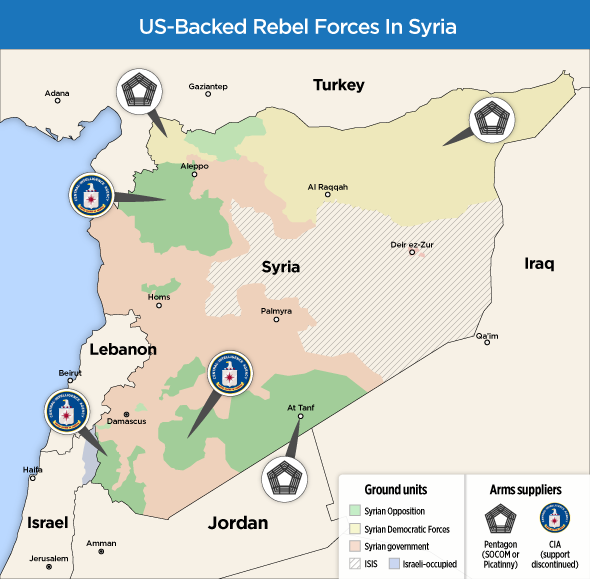

Reporters have pieced together the Pentagon’s complex supply line to Syria using procurement records, ship-tracking data, official reports, leaked emails, and interviews with insiders. This program is separate from a now-defunct CIA effort to arm rebels fighting Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad.

The Pentagon is buying the arms through two channels: the Special Operations Command (SOCOM), which oversees special operations across all services of the US military, and the Picatinny Arsenal, a little-known US Army weapons facility in New Jersey.

The munitions are being transported by both sea and air from Europe to Turkey, Jordan and Kuwait. They are then distributed to US allies in northern and southern Syria by plane and truck. (See: Black Sea Route)

Reporters discovered that the US is using vaguely worded legal documents which obscure Syria as the weapons’ final destination – a practice experts say threatens global efforts to combat arms trafficking and puts the Eastern European governments who sell the weapons and ammunition at risk of breaching international law. Others raise the issue of who, exactly, is using the arms and what will happen to them once ISIS has been defeated.

The Pentagon started the major buy-up in September 2015 under President Obama. By May this year, it had already spent more than $700 million on AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) launchers, mortars, and other weapons and ammunition.

More than $900 million has been contracted to be spent by 2022, and nearly $600 million more has been budgeted or requested by the Trump administration. This brings the grand total of the Pentagon’s intended spending on its Syrian allies to $2.2 billion.

This US-financed supply line is similar to a Saudi-backed €1.2 billion arms pipeline to Syria uncovered last year by BIRN and OCCRP.

Asked about the unprecedented purchase of Soviet-style arms for Syrian rebels, the Pentagon said that it had carefully vetted the recipients, adding that the equipment was provided “incrementally” and is the “minimum needed for the immediate mission.”

Syria Train and Equip: A Major Shift in Strategy

As ISIS swept across Syria in 2014, the Pentagon hastily launched a $500 million Syria Train and Equip program to build up a new force of rebels, armed with modern US weapons, in an attempt to counter the threat. SOCOM – the elite unit responsible for killing Osama Bin Laden – was tasked with buying the arms.

But nine months later, the program had collapsed, with only a few dozen recruits having made it onto the battlefield.

Amid a flurry of negative headlines, the Pentagon needed a new plan. Starting in September 2015, the US would focus not on building a new anti-ISIS army, but on arming rebels already on the ground.

While the Pentagon did not reveal the details of its new plan, a previously unreported spending request from February 2016 made clear that it would stop training new units and supplying them with modern weapons. Instead, it would select “vetted” opposition forces already on the ground and send them Soviet-style weapons and ammunition they were already using and familiar with.

The first delivery, which included 50 tons of ammunition and rocket-propelled grenades, arrived in October 2015, just a month after the shift in policy. The munitions were airdropped to the Kurdish-dominated coalition within the Syrian Democratic Forces currently spearheading the fight to reclaim Raqqa.

Many more shipments followed.

By May 2017 – the latest date for which data is available – SOCOM would purchase $238.5 million in weapons and ammunition from Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Czech Republic, Kazakhstan, Poland, Romania, Serbia and Ukraine, according to an analysis of thousands of procurement records by BIRN and OCCRP. Prior to the start of the program, its spending on Eastern Bloc weaponry had been negligible.

SOCOM will buy an additional $172 million in arms this fiscal year. The shopping list includes tens of thousands of AK-47s and RPGs and hundreds of millions of pieces of ammunition, according to requests made by the Pentagon. An additional $412 million has been requested by the Trump administration or budgeted for 2018.

SOCOM has not previously acknowledged its role in the Syria Train and Equip program. In a written statement to BIRN and OCCRP, the Pentagon confirmed that the secretive unit was charged with procuring weapons and ammunition for Syrian rebels. SOCOM is also known to covertly supply US partners in other conflicts.

Picatinny: A New Supply Line Revealed

SOCOM is not the only Pentagon unit which has been procuring arms and ammunition for the Syria Train and Equip program.

The rest of the procurement is being handled by the Picatinny Arsenal, a US Army facility in New Jersey. Picatinny already has experience buying large quantities of Soviet-style arms (referred to in procurement documents as “non-standard weapons and ammunition”) for partner forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. These purchases are always clearly labelled with the end destination.

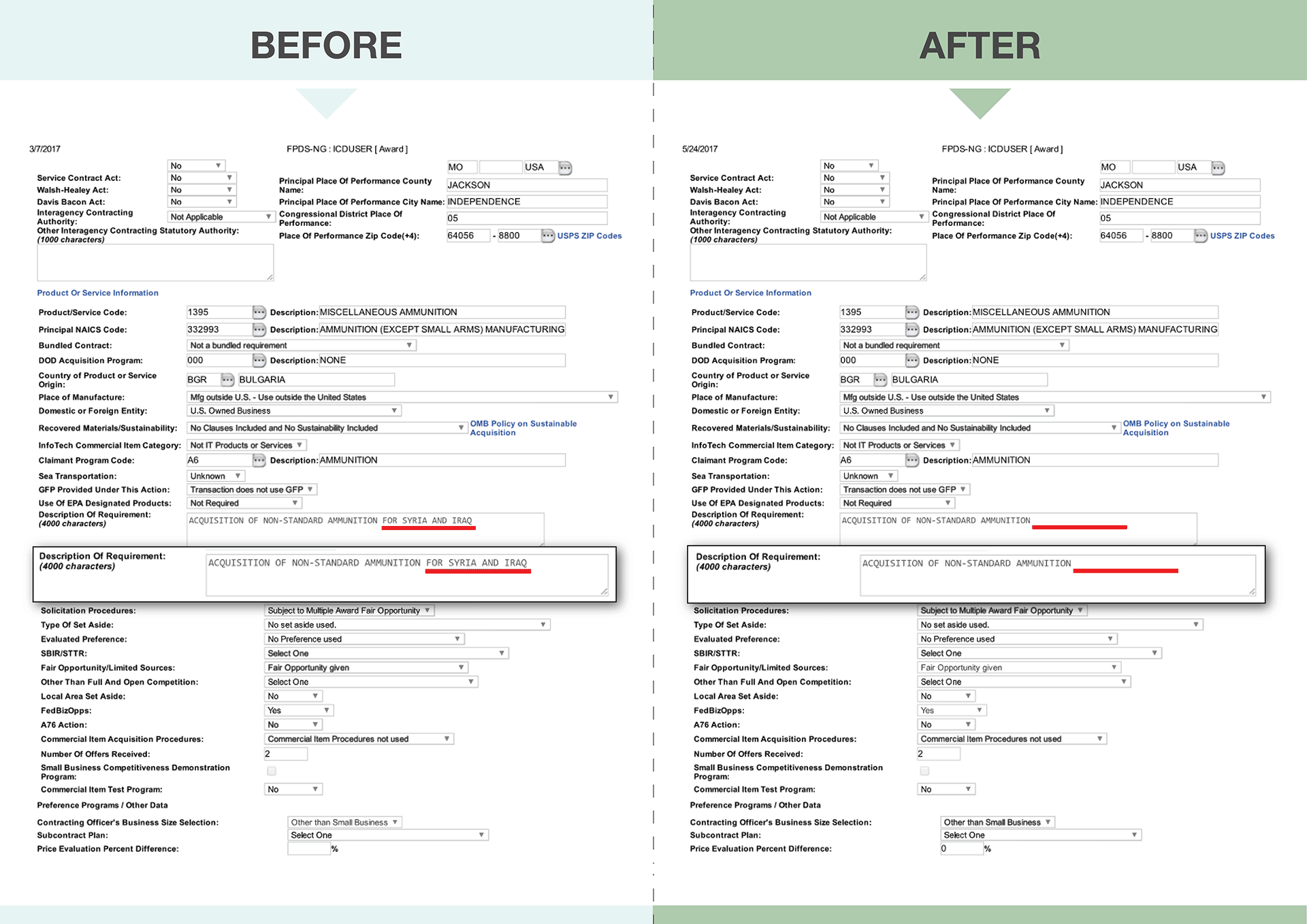

But one mysterious set of purchases – totaling $479.6 million – contains no end destination at all. An analysis of these procurement documents by BIRN and OCCRP reveals it is likely that much, if not all, of the arms in question are headed for Syria.

An important clue lay in seven of the contracts, signed in September 2016 and worth $71.6 million, which did initially cite Syria either by name or by the Pentagon’s internal code – V7 – for the Syria Train and Equip program. These references were deleted from the public record after BIRN and OCCRP asked the Pentagon about these deliveries this March.

Reporters made copies of the documents before they were deleted. The Pentagon has declined to explain the alterations.

Picatinny is circumspect about its role supplying Syrian rebels given the sensitive nature of the conflict. In addition to pitting an array of militias against Syrian government forces, the fighting is described by experts as a complex proxy war involving Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and Russia.

There is other evidence of Picatinny’s growing role in the Syria Train and Equip program.

A promotional story published on its website in December 2016 celebrated an internal Pentagon award for, among other successes, buying “significant quantities” of non-standard ammunition for Syria, as well as Iraq and Afghanistan.

A Picatinny presentation from March 2017 reveals that it will take over from SOCOM the role of procuring ammunition for the Syrian program. SOCOM will continue to buy weapons.

More than half of the $2.2 billion identified by BIRN and OCCRP has not yet been spent.

In March 2016, Picatinny tasked two military giants – Chemring, a British firm, and US-based Alliant Techsystems Operations (now part of Orbital ATK) – with procuring $750 million worth of ammunition on its behalf over the following five years, of which $372 million has yet to be spent. Another $500 million contract was awarded to Chemring, Alliant, and two other companies in August. On Picatinny’s website, the latter contract is specifically described as being intended to fight ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

With at least 50,000 US-supported rebels engaged in active combat, Syria is likely to absorb much of the contracted ammunition in the coming years, but some may be spent on other conflict zones where Soviet-style weapons are in use.

Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel

The newly revealed $2.2 billion pipeline financed by the US, as well as the earlier €1.2 billion pipeline financed by Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have meant boom times for arms producers in Central and Eastern Europe.

VMZ Sopot, a Bulgarian state-owned ammunitions factory and one of Picatinny’s main suppliers, announced in early 2016 that it planned to add 1,000 employees to its workforce that year. During the three months prior, it had already hired 500 new staff.

Factories in Serbia, such as Krusik, a missile manufacturer, have also drastically increased production. Aleksandar Vucic, then Serbia’s Prime Minister, boasted last year that Serbia could increase its output five times and still not meet demand.

As the thirst for Soviet-style weapons grows, the competition is becoming fiercer.

The US had traditionally turned to Romania and Bulgaria for non-standard armaments, but the surge in demand has forced contractors to look to the Czech Republic, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and now Ukraine, Georgia, Poland, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan and Croatia, according to US procurement records.

Scarce supplies have also forced the Pentagon to lower its standards for weapons and ammunition. Previously it had required suppliers to provide equipment less than five years old, but in February it dropped this requirement for some types of weapons and ammunition, according to official documents obtained by BIRN and OCCRP.

Munitions stored in poor conditions degrade, sometimes becoming unusable or even dangerous. A Pentagon contractor due to train Syrian rebels died in June 2015 when the decades-old RPG he was handling exploded at a firing range in Bulgaria. Nevertheless, the Pentagon has continued to use the contractor that supplied the faulty weapons.

There are other problems, too. Reporters have found that directors of three contractors it uses, and the president of a critical sub-contractor, have faced serious questions about their integrity, including one who bragged about paying “commissions” to foreign agents to secure deals. Another subcontractor employed a firm with links to organized crime.

Undermining the Arms Control System

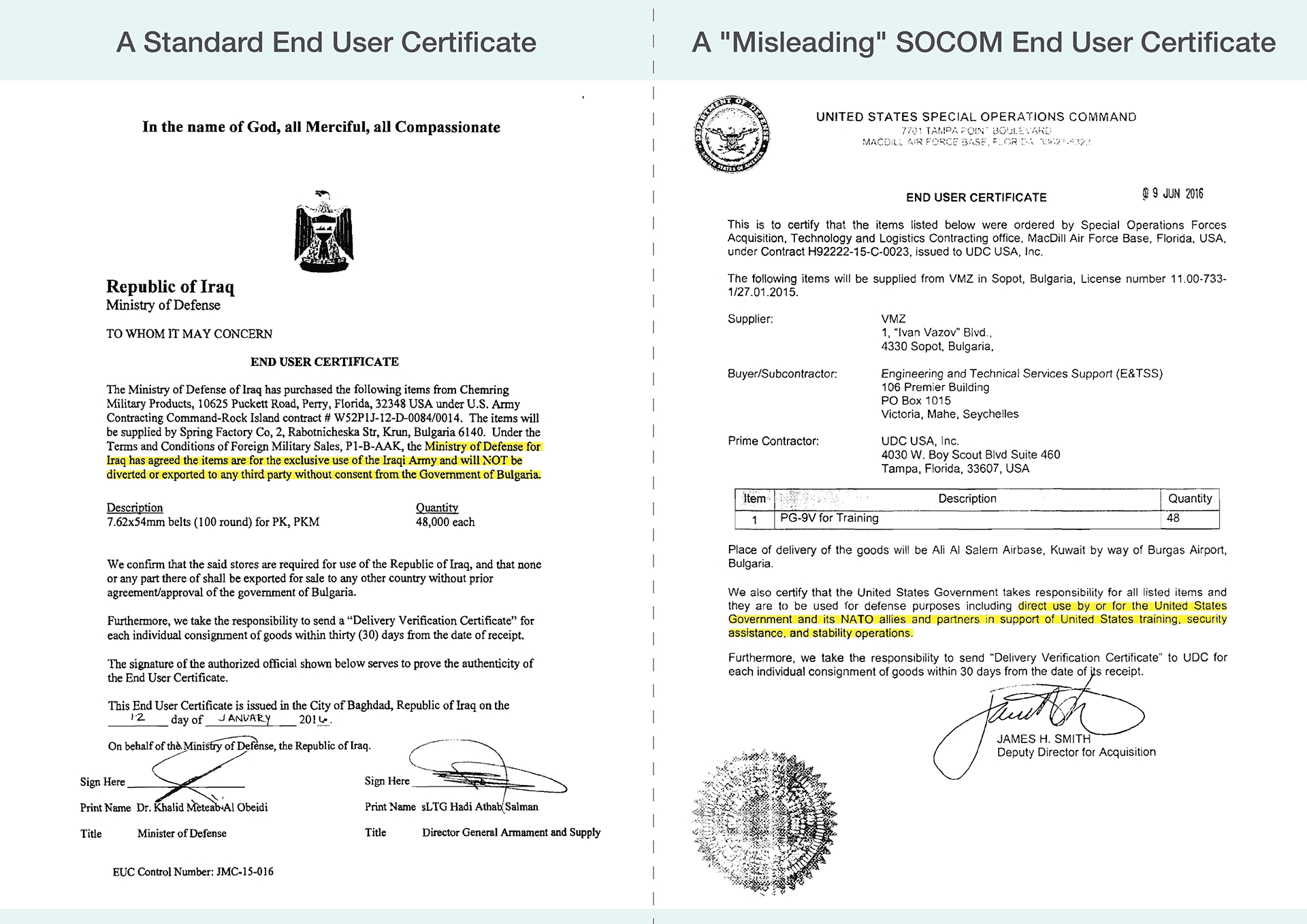

In supplying the Syrian rebels, the Pentagon has used highly unusual and misleading legal documentation that exploits a loophole in the system designed to prevent diversions of arms to terrorists, embargoed groups, or war criminals.

To secure an arms export license, buyers must provide a valid end-user certificate guaranteeing the weapons’ final destination.

But a certificate issued by SOCOM under the Syria program and seen by reporters does not mention Syria as the final destination. Instead, it lists SOCOM as the final user.

The document states that “the material will be used for defense purposes in direct use by US government, transferred by means of grants as military education or training program or security assistance.”

The statement allows SOCOM to divert the equipment to any army or militia to whom it is providing security assistance, including Syrian rebels, according to arms control experts who have reviewed the evidence.

In a detailed written response, the Pentagon did not dispute its designation of the US Army as the end user, but explained that the certificates citing “security assistance” cover transfers to foreign fighters.

“We expect any partnered force or security assistance recipient to use the materiel as intended, i.e. for the counter-ISIS fight, and we monitor their usage to ensure they comply,” a Pentagon spokesman said.

But arms experts criticized this practice, describing it as a danger to the global arms control system.

Roy Isbister, an expert on arms transfers at Saferworld, a non-governmental organization that works to prevent violent conflict, said, “The [end-user] system relies on clarity and diligence. If the US is manipulating the process and providing cover for others to claim ignorance of the end users of the weapons in question, the whole control system is at risk.”

Patrick Wilcken, a researcher on arms control and human rights at Amnesty International, described SOCOM’s end-user certificate as “very misleading.”

“An end user certificate that did not contain [the final destination] would be self-defeating and highly unusual,” he said. “The US is undermining the object and purpose of the ATT (United Nations Arms Trade Treaty).”

Wilcken explained that, while Washington has not yet ratified the agreement, and is therefore not legally bound by it, as a signatory it is expected not to undermine it.

As a member of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Washington has signed a series of measures to prevent weapons trafficking – including a binding decision that end-user certificates include the final destination country.

European exporter states have ratified the ATT and are also bound both by the OSCE’s decisions and the EU’s even stricter rules, known as the Common Position on Arms Exports. Most prospective members have already adopted these rules.

The Romanian, Czech, Bosnian, and Serbian governments confirmed that they had granted export licenses with the US – not Syria – listed as the final destination.

Georgia’s Ministry of Defense said that an export deal was under negotiation but it had not yet received an end-user certificate from the Pentagon and no contract had been signed.

Poland and Croatia said it had not approved any exports to Syrian rebels.

Officials from Ukraine, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, and Afghanistan did not respond to requests for comment.

Under the ATT and the EU Common Position, exporters must take action to prevent arms and ammunition from being diverted and used to commit war crimes or “undermine peace and security.”

Without knowing the final destination, such an assessment is impossible.

Wilcken said that Amnesty International was especially concerned that the US is supplying the Syrian Democratic Forces, given evidence that one of its largest component forces, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), had “razed villages,” an act Amnesty described as a war crime.

Wilcken said that such a vast inflow of weaponry raised fears about the future of the Middle East.

“Given the very complex, fluid situation in Syria … and the existence of many armed groups accused of serious abuses,” he said, “it is difficult to see how the US could ensure arms sent to the region would not be misused.”

Additional reporting from Anna Babinets, Nino Bakradze, Aubrey Belford, David Bloss, Roberto Capocelli, Maria Cheresheva, Pavla Holcova, Roxana Jipa, Frederik Obermaier and Atanas Tchobanov.