This material belongs to: InSight Crime.

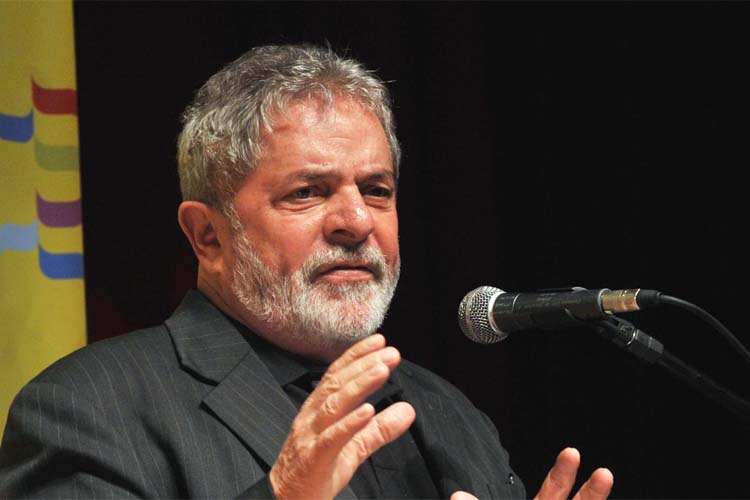

On the surface, former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva‘s 9-year sentence for corruption seems reminiscent of numerous corruption cases targeting former or current presidents in Latin America. But behind the accusations are varying degrees of collusion and control, from heading a criminal enterprise to a one-off criminal act of personal enrichment.

The still-popular Brazilian politician may eventually see judge Sergio Moro‘s sentence overturned by an appeals court. But as it stood on July 12, Lula was guilty of laundering money and accepting bribes from the Brazilian construction giant OAS during his 2003 to 2011 term in office.

In return for these kickbacks, valued at $1.1 million and paid via renovations to one of Lula’s apartments, the then-president helped OAS secure public contracts from Petrobras, the Brazilian state oil company. Lula will remain free while he appeals the sentence. He is currently facing four other ongoing criminal proceedings.

Lula is not the only one facing such charges. The so-called “Lava Jato,” or “Car Wash,” scandal that swallowed the one-time union leader turned charismatic president and world leader also swallowed numerous other officials as Brazil‘s construction conglomerates gave generous kickbacks in return for lucrative contracts with the then-expanding company.

Kickback schemes like these are typical in Latin America. But not all corruption is equal. While Lula may have taken part in what Moro called “systemic corruption,” he did not necessarily head up the scheme as some of his regional counterparts did.

With that in mind, we have broken up these examples into three major categories in our attempt to create a typology for these presidential cases.

1) Top-down Corruption

The first category is top-down corruption. This is where the executive is the clear leader of the scheme, the person who is directing the other parts of the network involved in the conspiracy.

In this regard, the best example is former Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina. The former president is accused of orchestrating two corruption schemes during his short time in office from 2012 to 2015, including one that revolved around government contracts as a form of reimbursement for his electoral campaign’s donors, and another in which the president oversaw a system that methodically defrauded customs offices. He is currently in jail as his case proceeds through the court system in that country.

A military officer before turning to politics, Pérez Molina set up what amounted to a mafia state. As InSight Crime explained in detail, corruption during Pérez Molina’s presidency was defined by a vertically integrated system in which the former general looked out for the economic interests of shady networks and, of course, himself.

Another example is Argentina‘s former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who served from 2007 to 2015. Kirchner was charged in April 2017 for “taking part in a criminal association in the role of chief,” according to judicial records. Specifically, prosecutors say Kirchner granted public contracts in exchange for kickbacks, generally paid via the rental of hotel rooms and properties owned by the Kirchner family.

Prosecutors say it was part of clear pattern, as evidenced by similar charges in a second and a third case. For 12 years, these prosecutors claim, Kirchner and her late husband, Néstor Kirchner (who preceded his wife as president from 2003 to 2007), systematically favored a tightknit group of businessmen, who were granted a disproportionate share of often overpriced and seldom completed public works contracts, in exchange for contributing to the Kirchners’ personal wealth. The family’s coffers grew by 850 percent during Nestor and Cristina’s presidencies, reported Clarín. Néstor Kirchner died in 2010. Cristina Kirchner, who is awaiting trial, claims she is the innocent victim of a political witch hunt.

A third, albeit less clear-cut case of top-down management, is that of Panama‘s former President Ricardo Martinelli. Prosecutors say Martinelli was the head of an espionage ring that surveyed more than 150 people illegally, including political opponents and business competitors. Martinelli is also accused of diverting more than $13 million from welfare programs. The former executive fled the country, but in June 2017, he was arrested in the United States and is now battling his extradition.

2) Participatory Corruption

More often than not, charges against current or former regional presidents suggest the suspect simply made the most of a pre-existing political environment heavily infiltrated by criminal and corrupt networks, or by exploiting longstanding mechanisms meant to favor the interests of a few. The president naturally receives a hefty reward in the process, but more importantly the official maintains a political environment or a governing system in which organized crime and corruption holds sway. Lula’s case seems to fit into this category.

Another example is Brazil‘s current President Michel Temer, who was charged in June this year for accepting bribes in the “Lava Jato” scandal rocking Brazil‘s political elite. The judiciary needs a two-thirds vote from congress to go forth with proceedings, but credible evidence indicates that Temer took part in the massive scheme.

Brazil’s corrupt environment even spread to other countries. Peruvian authorities are seeking the arrest of the country’s president from 2001 to 2006, Alejandro Toledo, after charging him with money laundering. The former leader is accused of helping the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht secure public contracts in exchange for kickbacks worth $20 million. It is one of many cases connected to Odebrecht, which set up a special department dedicated to handling bribes and has become the poster boy for corruption around the region.

Another former Peruvian president, Ollanta Humala, and his wife Nadine Heredia were remanded to preventative detention on July 13 as prosecutors investigate the couple for related accusations.

Meanwhile, certain presidential misconduct carried out within a broader criminalized system appears to serve the interests of political rather than economic entities. El Salvador‘s former President Antonio Saca, who served from 2004 to 2009, for instance, was arrested in October 2016 for siphoning government funds into a “secret account” thought to have been used by politicians to embezzle money for years, reported El Faro. The charges he faces are money laundering, embezzlement and criminal association.

As for Saca’s predecessor, former President Francisco Flores — whose term lasted from 1999 to 2004 — he was set to stand trial on four separate charges before his death in January 2016. One charge asserted that Flores redirected $10 million from Taiwanese international relief aid to his political party, part of which would eventually serve to fund Saca’s successful 2004 election bid.

3) The One-off

The last type of case is the one-off, the classic crime of opportunity that provides its participants with a windfall but is not necessarily part of a prolonged scheme. This type of graft, however, is sometimes hard to separate from the other two since it often depends on having a corrupt system in place.

For example, the president of Guatemala from 2000 to 2004, Alfonso Portillo, pled guilty in March 2014 in a US court to laundering $2.5 million in bribes from the government of Taiwan, in exchange for maintaining Guatemala‘s diplomatic recognition of the country. There is no evidence so far that this scheme was iterated or part of a larger, structured operation.

However, the bribe did occur within a broader environment of government corruption. Portillo’s administration was connected to another, more prolonged scheme of corruption and organized crime that was embezzling money from the country’s military. And while the US plea bargain eventually focused on the Taiwanese bribe, the original indictment charged Portillo with laundering more than $70 million from various sources.